Salafi Jihadi Weekly Update (2023–Feb 15, 2024)

Salafi Jihadi Weekly Update (2023–Feb 15, 2024)

Research

MIDDLE EAST

ISIS

The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa as of February 2024

MIDDLE EAST

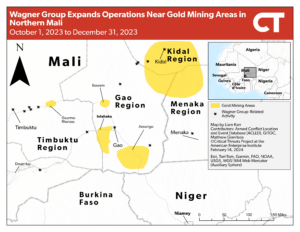

RUSSIA IN AFRICA

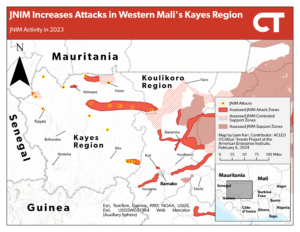

Jnim Increases Attacks in Western Mali’s Kayes Region

MIDDLE EAST

RUSSIA IN AFRICA

Coups Spread Across An African ‘coup Belt’

MIDDLE EAST

ISIS

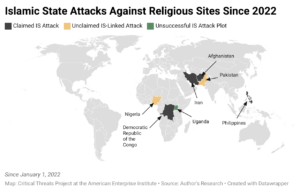

Islamic State Attacks Against Religious Sites Since 2022

MIDDLE EAST

ISIS

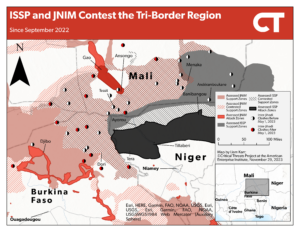

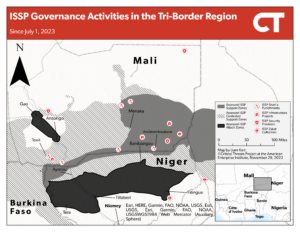

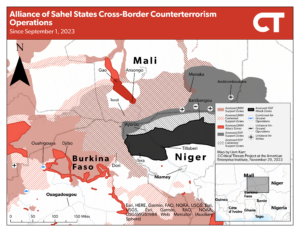

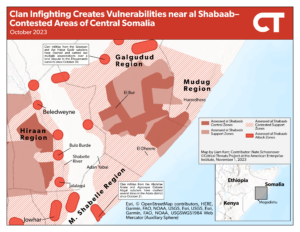

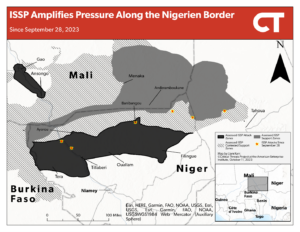

Issp and JNIM Contest the Tri-border Region Since September 2022

MIDDLE EAST

ISIS

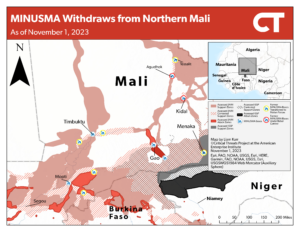

Minusma Withdraws from Northern Mali as of November 1, 2023

MIDDLE EAST

AFGHANISTANIRAQISISSYRIA

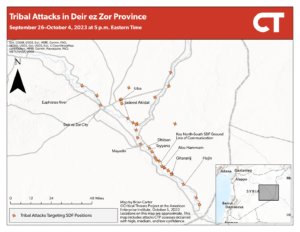

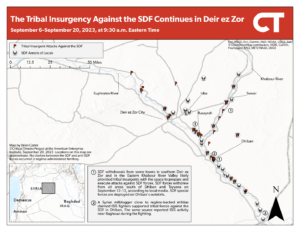

Tribal Attacks in Deir Ez Zor Province September 26–october 4, 2023 at 5 P.m. Eastern Time

MIDDLE EAST

AFGHANISTANIRAQISISSYRIA

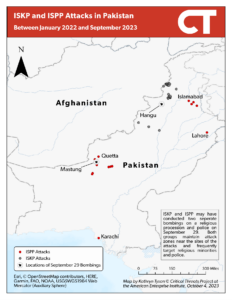

Iskp and ISPP Attacks in Pakistan Between January 2022 and September 2023

MIDDLE EAST

AFGHANISTAN

Haqqani Network–affiliated Governors in Afghanistan September 20, 2023

MIDDLE EAST

AFGHANISTANIRAQISISSYRIA

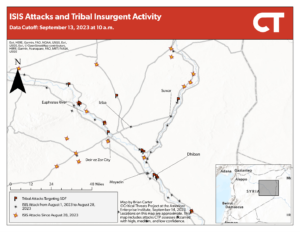

Isis Attacks and Tribal Insurgent Activity Data Cutoff: September 13, 2023 at 10 A.m.

MIDDLE EAST

AFGHANISTANIRAQISISSYRIA

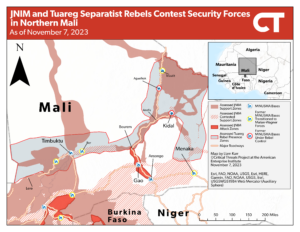

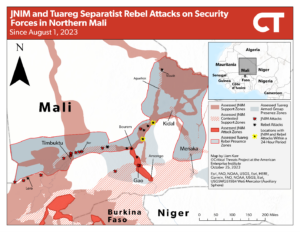

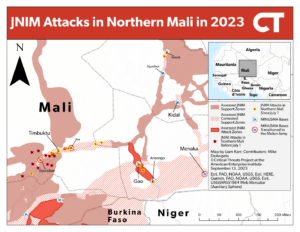

Jnim Attacks in Northern Mali in 2023

MIDDLE EAST

AFGHANISTANIRAQISISSYRIA

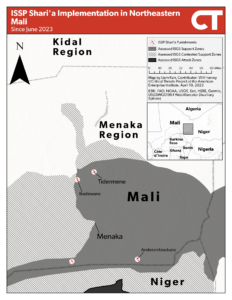

Issp Shari’a Implementation in Northeastern Mali Since June 2023

MIDDLE EAST

AFGHANISTANIRAQISISSYRIA

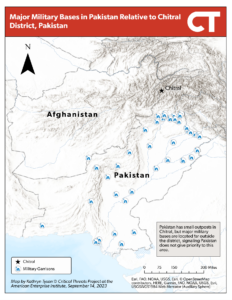

Major Military Bases in Pakistan Relative To Chitral District, Pakistan

MIDDLE EAST

AFGHANISTANIRAQISISSYRIA

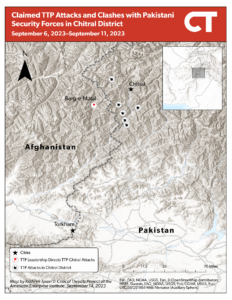

Claimed TTP Attacks and Clashes With Pakistani Security Forces in Chitral District September 6, 2023–september 11, 2023

MIDDLE EAST

AFGHANISTAN

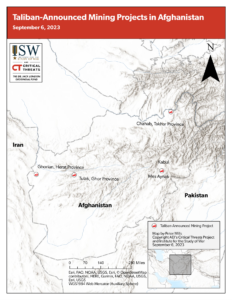

Taliban-announced Mining Projects in Afghanistan September 6, 2023

MIDDLE EAST

AFGHANISTANIRAQISISSYRIA

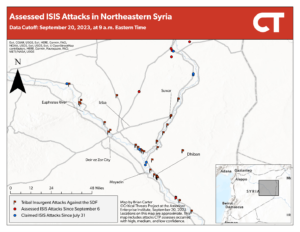

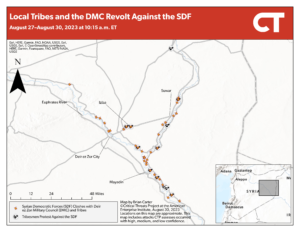

Local Tribes and the Dmc Revolt Against the SDF August 27–august 30, 2023 at 10:15 A.m. ET

MIDDLE EAST

AFGHANISTANIRAQISISSYRIA

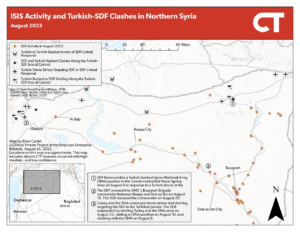

Isis Activity and Turkish-sdf Clashes in Northern Syria August 2023

MIDDLE EAST

ISIS

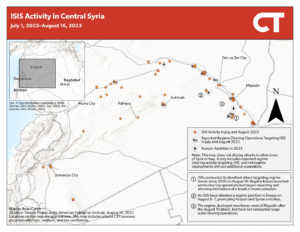

Isis Activity in Central Syria July 1, 2023–august 16, 2023

Middle East

ISIS

The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa as of February 2024

Middle East

Russia in Africa

Jnim Increases Attacks in Western Mali’s Kayes Region

Middle East

Russia in Africa