Newsroom

Global Resonance

ISW in the News

Welcome to the ISW Newsroom, where you can stay up to date on the latest news and announcements, learn about and sign up for events, and browse featured media coverage.

December 31, 2024

Ukraine: How the war shifted in 2024

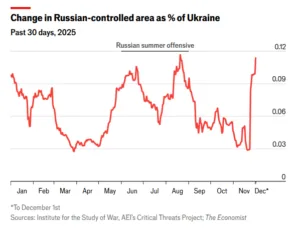

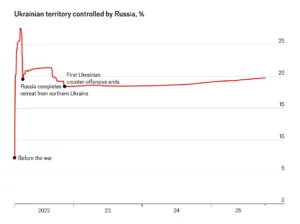

“2024 saw more battlefield movement than 2023, though according to data provided by the Institute for the Study of War, this was largely seen in the second half of the year, a price for which Russian paid heavily.”

— Fox News

December 28, 2024

U.S. and Ukrainian intelligence reveals more about North Korean soldiers fighting for Russia

“The Russians are struggling to offset that 30,000 casualties per month figure. They basically have a system that’s allowed them to be able to withstand and sustain that for the last two and a half years, but it’s not working anymore. The North Koreans provided 10 days’ worth of casualties with that initial 10K investment.”

— NPR

December 27, 2024

Ukraine Risks Losing All the Russian Land It Seized Within Months, US Officials Say

“It’s always been clear that Russia could retake Kursk if it chose to, said George Barros, who leads the Russia and Geospatial Intelligence teams at the Institute for the Study of War. But the Kursk incursion has shown that Russia’s international border isn’t fully protected and could be breached again at other points, he said, and that using US-made equipment inside Russia didn’t result in catastrophic escalation.””It’s always been clear that Russia could retake Kursk if it chose to, said George Barros, who leads the Russia and Geospatial Intelligence teams at the Institute for the Study of War. But the Kursk incursion has shown that Russia’s international border isn’t fully protected and could be breached again at other points, he said, and that using US-made equipment inside Russia didn’t result in catastrophic escalation.”

— Bloomberg

December 20, 2024

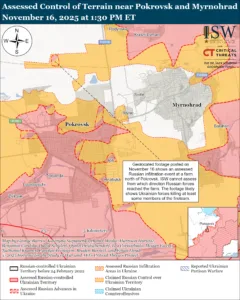

What Would The Russian Capture Of Pokrovsk Mean For The Ukraine War?

“If the Russians do seize Pokrovsk, the current campaign will likely culminate due to force and resource constraints, Barros says.”

— RADIO FREE EUROPE Radio Liberty

December 19, 2024

INTERVIEW | The Changing Face of War in Ukraine with Kimberly Kagan

— Japan Forward

December 17, 2024

Russia Withdraws Air-Defense Systems, Other Advanced Weaponry From Syria to Libya

— Wall Street Journal

December 16, 2024

In Conversation: An Evening with Oleksandra Matviichuk and Kimberly Kagan

— Ukrainian Institute of America

December 12, 2024

Biden Has a Pair of Gifts for Trump

“And, crucially, the fighting in Ukraine helped weaken Syria. This was perhaps the most surprising aspect of my conversations about the present situation. Every expert I talked to said that Ukraine helped facilitate the fall of the Assad regime by, in Kimberly Kagan’s words, taking the Wagner Group ‘“’off the chess board.’”

— The New York Times

December 11, 2024

Russia tie-up sparks fears of modernized North Korean defense industry

“One of the benefits that Putin surely hopes to gain from this deepening cooperation with North Korea is an increasing ability to leverage North Korea’s industry and industrial production that, I think will have important ramifications — not only for the war in Ukraine, but also all over the Asia-Pacific and frankly, in Europe as well,” according to Kimberly Kagan, president and founder of the Institute for the Study of War (ISW), a research group that publishes daily updates on the Ukraine conflict.”

— Japan Times

December 5, 2024

Far from the front lines, a spy war rages over Russian weapons

“Russia is compensating by scavenging parts from old Soviet-era tanks and howitzers. But satellite photos of Russian motor pools and scrapyards show that reserves of old tanks are being rapidly depleted, said George Barros, Russia team leader at the Institute for the Study of War.”

— Washington Post

For the press

Lorem ipsum odor amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit. Sed sed mi lacus sollicitudin dapibus elit fringilla a turpis.

name

company

details

ISW’S IMPACT

media coverage

Browse featured media coverage and ISW news curated by the ISW press team.

Search

Date

Category

Team

Request an Interview

ISW and its analysts are frequently featured in leading US and international media outlets. For media inquiries or to request an interview with an ISW expert, please contact our Press Team at [email protected].

To receive the latest ISW publications and updates directly in your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters using the form below.

Request an Interview

ISW and its analysts are frequently featured in leading US and international media outlets. For media inquiries or to request an interview with an ISW expert, please contact our Press Team at [email protected].

To receive the latest ISW publications and updates directly in your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters using the form below.