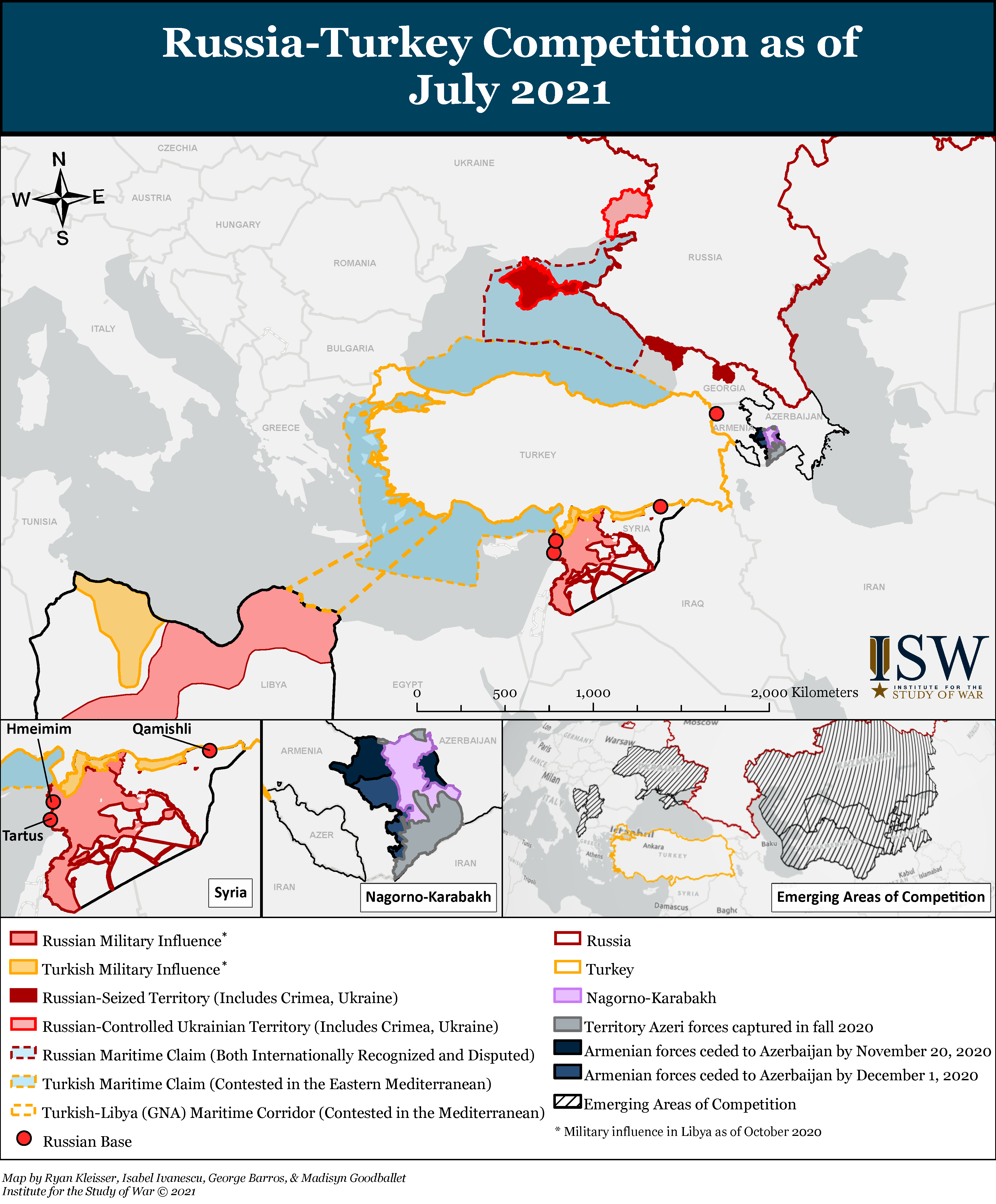

Key Takeaway: The Russo-Turkish relationship has become a defining driver of conflict in a vast region from North Africa to Central Asia. Turkey and Russia’s shared objective to make the current international system more multipolar leads them to cooperate in many areas, but differences in desired outcomes have led to more frequent confrontations in Syria and the Caucasus. Both states’ ability to compartmentalize their cooperative and competitive activities will likely determine the degree of instability caused by their assertive foreign policies. The United States and its allies must find the right avenues of cooperation with Turkey to counter Russian influence and limit the risk of rapid cross-theater escalation between the Kremlin and Ankara.

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan share an opposition to the current Western-led international order. Erdogan wants to transform Turkey into an independent and influential global power while remaining a key member of NATO. He sees engagement with Russia as crucial to expand Turkey’s reach and diversify its partners beyond the West. Putin wants to undermine Western-led institutions and reestablish Russia as an essential actor in a multipolar world. Putin sees Turkey’s goal of strategic independence as instrumental to exacerbating policy divisions in the West and undermining NATO.

Russia and Turkey effectively compartmentalize their conflicts. Russia and Turkey successfully maintain regular diplomatic contact despite supporting opposing sides of conflicts in Syria, Libya, and to a limited extent Nagorno-Karabakh. These channels have remained intact through geopolitical crises or escalations that might have caused other nations in similar positions to cut off diplomatic relations.

Most Russo-Turkish competition occurs near both countries’ most important regions of interest, not in far-flung territories. Turkey increasingly threatens Russia’s core sphere of influence through cultural and military outreach to Turkic-Muslim communities of the former Soviet Union and other areas with major Russian interests.[1] Russia can restrict Ankara’s behavior in Syria with the threat of a pro-regime offensive in Idlib province on Turkey’s border. A Russian offensive could drive 3-million Syrians to flee north—perhaps the biggest danger to Turkey’s already struggling economy and Erdogan’s electoral support. Russia remains the key powerbroker in the Caucasus after brokering the Armenia-Azerbaijan ceasefire in November 2020. The Kremlin may prioritize increasingly hostile policies toward Turkey in response to Turkish actions in theaters close to the Kremlin’s core interests.

Both states are increasingly willing to intervene in conflicts and crises abroad to their advantage. The Kremlin wants to retain dominance in the former Soviet Union (FSU), increase Russia’s ability to project force globally, and expand Russian economic assets and basing in the Middle East. These actions often oppose Ankara’s effort to strengthen Turkish leadership in its near abroad, the Turkic-Muslim world, and among sympathetic developing countries in sub-Saharan Africa and in the rest of Asia. Turkey is also increasingly willing to deploy its armed forces and military equipment abroad to shape conflicts to its own advantage—exemplified in Libya and Nagorno-Karabakh: Turkey’s military support encouraged and enabled Azerbaijan’s offensive in Nagorno Karabakh in late 2020, providing a low-cost opportunity to increase Turkey’s role in the Caucasus and open a new theater of competition with Russia. Similarly, Turkey’s combination of drone use, proxy force deployments, and military advising shifted the balance of forces in Libya to Turkish-backed forces’ advantage in early 2020.

Russia and Turkey’s expanding deployment of conventional and proxy forces increases the risk of escalation in several theaters. Russia and Turkey’s use of foreign proxy forces, complex airpower, including unmanned aerial vehicles, and will to transform local conflicts into international frontlines have built a fragile international web of Turkish-Russian interactions—including Ukraine, Central Asia, and the Black Sea. Either actor can escalate in one theater in response to actions in another theater. Both seek low-cost opportunities to disrupt the other when necessary and offer concessions at other times to maximize their leverage in different theaters. For example, Russia conducted high-casualty airstrikes against the Turkish-backed Syrian factions after reports of Turkish recruitment and deployment of Syrians to Azerbaijan in support of Baku’s Nagorno-Karabakh campaign.[2]

The United States and its allies will need to operate around this complex dynamic for years to come. Ankara will remain dependent on NATO for many of its security requirements even while carving out a more independent and influential role. Both of these aspects of Turkish strategy predate Erdogan and will likely outlast his government. If US and allied policymakers understand Turkey’s unique strategic calculus, the NATO alliance and the US-Turkey partnership can find the right avenues of cooperation to counter Russian influence in key theaters and limit the risk of rapid cross-theater escalation between Russia and Turkey.

[1] https://www.tccb.gov.tr/en/news/542/128493/president-erdogan-meets-with-president-minnikhanov-of-tatarstan

https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/diplomacy/fm-cavusoglu-meets-with-ukrainian-pm-leader-of-crimean-tatars-pledges-turkeys-support

https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/diplomacy/turkish-support-for-moldovas-gagauzia-priceless-governor-vlah

https://apnews.com/article/azerbaijan-middle-east-europe-turkey-government-and-politics-26ac0104ab11d7403b6eb9a0ff99351e

[2] https://apnews.com/article/turkey-syria-middle-east-e4a5fcaf654d79de51dc431e77b4e46f

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-armenia-azerbaijan-turkey-syria/turkey-deploying-syrian-fighters-to-help-ally-azerbaijan-two-fighters-say-idUSKBN26J25A