|

|

The Lands Ukraine Must Liberate

The Lands Ukraine Must Liberate

Frederick W. Kagan, George Barros, Noel Mikkelsen, and Daniel Mealie

December 31, 2023

A Ukraine strong enough to deter and defeat any future Russian aggression with an economy strong enough to prosper without large amounts of foreign aid is the only outcome of Russia’s war that the United States and the West should accept. Trusting Russian promises of good behavior would be foolish. Leaving Ukraine’s economy badly damaged would create a long-term and large drain on Western finances. Discussions about pressing Ukraine to trade land the Russians now occupy for a ceasefire or armistice have garnered attention recently, based on rumors of Kremlin interest in negotiations of some sort.[1] These discussions have thus far largely focused on the supposed intransigence of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky who, it is argued, must be pressed to accept that Ukraine must cede some of its territory. That argument ignores the question that should be central to any such discussion: what are the concrete military, economic, and financial consequences that these territorial sacrifices would have for Ukraine’s long-term security and economic viability or for the future financial burden they would impose on the supporters of an independent Ukraine? The serious evaluation of this question shows that there are real military and economic reasons for Ukraine to try to liberate all of the territory Russia now occupies and that, in any event, the current lines cannot be the basis for any settlement remotely acceptable to Ukraine or the West.

Russia Will Not Abandon Its Maximalist Aims Now or in the Future

Russian President Vladimir Putin and many Kremlin officials have driven deep into the Russian political consciousness the ideas that Ukraine has no independent identity and no basis to continue to exist as an independent state; that any Ukrainian government not totally subservient to Moscow is a pawn of the West and a threat to Russia; that Ukrainian opponents of Russian rule are Nazis intent on conducting genocide against Russians in Ukraine; and that Russia has a legal, moral, and religious obligation to extirpate these supposed threats and restore Ukraine to its rightful place as a historically Russian land.[2] Putin has made these arguments part of his 2024 presidential election platform.[3] Russian administrators are inserting them in curricula throughout Russia and occupied Ukraine.[4] Kremlin mouthpieces speak to the Russian domestic audience with one voice along these lines.[5] Putin is training Russians to commit themselves to the task of subjugating Ukraine, and that training will neither stop nor vanish following some negotiated ceasefire. It will, in fact, shape the thoughts and likely policies of Putin’s successors for years or decades.

The task facing Ukraine and the West, therefore, is to be prepared after the end of this conflict to confront a Russia still determined to achieve its original aims, likely fortified in that determination by a desire to avenge its failures in the course of this war. The damage that the current war is doing to Russia’s military helps to reduce the risks of Russia renewing war quickly, but that effect is temporary and its duration depends in large part on how committed Putin is to rebuilding Russia’s military capabilities rapidly. The Russia-Ukraine frontier will thus be a frontier of potentially imminent conflict for the indefinite future, unfortunately. Peace can only be sustained at an acceptable price if that frontier is defensible by the kinds of forces Ukraine can sustain over the long term.

The Forces Required to Defend Ukraine Depend on Ukraine’s Borders

Military requirements to defend a state depend on many factors including the likely strength and capability of the adversary, the length and configuration of the borders to be held, and the amount of depth the borders provide—that is, the degree to which the defender can temporarily give ground in the face of an attack. Ukraine and the West have little control after the fighting stops over the size and strength of the Russian military, which all current indications suggest will be much greater in a few years than it was in February 2022 by every measure.[6] They can control the other two factors, however, by committing to or refraining from trying to liberate additional Russian-occupied territory.

The amount of depth provided by any given border configuration is far more important than limited changes in the length of the lines in determining the military requirements of the defense and the cost of money, equipment, and social sacrifice needed to hold them. The more the defender must hold the initial line of defense at all costs the more he must maintain large and fully combat-capable forces near that initial line at all times. Sustaining a large, fully-equipped, fight-tonight-trained military is exorbitantly expensive and requires keeping a high proportion of the defender’s population in the military even during peacetime. Keeping many people mobilized all the time imposes a double cost on the state—it must pay each individual for their service, on the one hand, and it loses the contributions of that individual to the economy on the other.

A far more economical approach to defense is to hold a line with smaller forces intended not to defend but rather to delay the attacker’s advance to buy time for reserves of personnel and equipment to be called up and sent forward. Those reserves can then stop and reverse the initial attack, winning back any ground that has been temporarily lost. Reserves are far less expensive than mobilized troops—the defender pays the cost of calling them up and training them to begin with and of some refresher training after their initial service period is done, but they otherwise live normal lives contributing to the economy and raising families.

The land itself, of course, also contributes to the economy. In Ukraine’s case it often does so directly through agriculture and mining, but different frontline configurations can cede more or less of Ukraine’s industrial and other economic potential to Russia—weakening the Ukrainian economy and ability to sustain its military and strengthening Russia’s.

The January 2022 Lines Are Far Easier to Defend Efficiently than the December 2023 Lines

Ukraine’s borders and the line of contact between Ukraine and Russia before the full-scale invasion of 2022 were long—about 3,120 kilometers—but included large areas offering considerable defensive depth, especially in the northeast. Ukraine will always need to defend its northern border, opposite Belarus and then Russia, very close to the border itself on a west-to-east line extending from the Polish border to around Chernihiv. Kyiv is only about 100 kilometers from the border, and essential ground lines of communication run through Rivne and Lutsk at about the same distance. Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second largest city, is even closer to the international border and affords no depth at all. The Russian occupation in 2014 of eastern Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts and Crimea brought several other important Ukrainian cities under permanent threat. Mariupol was almost right on the line of contact in 2022.

In January 2022, Kherson and Melitopol were respectively about 90 and 115 kilometers away from Russian control. Their physical situation offers a better prospect for a more efficient defense, however. Kherson lies across the Dnipro River from Crimea, on the one hand, affording the Ukrainians in principle opportunities to fall back to the river line if necessary in the face of renewed Russian attack from there. Melitopol benefits from no such natural defenses, but Russian forces attacking from Crimea must cross several bridges to get to the Ukrainian mainland (a factor from which Kherson also benefits), creating chokepoints that could be used to slow the Russian advance and buy time for Ukrainian reserves to arrive. (That this did not happen in 2022 reflects the fact that, contrary to Russian claims, Ukraine was not preparing for a war with Russia before the full-scale Russian invasion. A future Ukrainian military surely will. Ukraine had fewer armed forces in these areas in 2022 because it had concentrated its best forces in the east opposite occupied Donbas. A future Ukrainian military will likely concentrate differently.)

Northeastern Ukraine offers even more depth. It is among the most fertile lands anywhere in the world but also sparsely populated, especially near the international border:

The terrain provides ample opportunity for delaying actions behind which reserves can mobilize to defend more heavily populated settlements in the rear and prepare to regain ground lost in an initial renewed, Russian assault.

The task of defending these long lines, even with the areas providing strategic depth, is daunting. The future Ukrainian military will have to be much larger and much better trained and equipped than it was in 2022. But it is far less daunting than the challenge Ukraine would face in having to defend the current lines if the conflict were frozen today. We will consider below the reduction in requirements that come from regaining the internationally recognized borders.

Freezing the Lines Unfreezes the Forces

Russian forces on the line of contact today are making marginal gains at a high cost in lives and materiel. A future Russian attempted invasion following a protracted period of reconstitution would not present the Russians with the same challenges.

The current Ukrainian and Russian deployments along the line are shaped by the ongoing active fighting, constraining Russian forces’ ability to optimize their deployments across the theater.[7] Russian forces are concentrated in areas they are focused on trying to seize at the moment, such as Avdiivka. Both sides have pulled artillery, air defense, aviation, and other scarce but vital systems as far out of range of the other’s strike capabilities as possible. Both sides have generally learned the hard way to avoid massing large quantities of tanks, armored personnel carriers, and other such weapons of war because doing so usually leads to their rapid destruction by massed artillery, drone, or air attack.[8] The ongoing fighting is consuming Russian forces generated just about as rapidly as Russia puts them into the field.

Should an armistice be established, however, few of the conditions shaping the deployments of these forces would hold anymore. New Russian forces would not be consumed by fighting after a ceasefire. The Russians would no longer be forced to mass in particular areas where they are currently attacking but would instead be able to rearrange their forces to optimize for other factors. They would be able to mass artillery, air defense, electronic warfare, and engineering capabilities, specifically bridging equipment, and other supplies in fortified defensive positions near the front line—something they cannot do now as Ukrainian forces attack any concentrations within range of their weapons systems when they see them. The Russians would be able to prepare, train, equip, and deploy reserves in echelons throughout southern and eastern Ukraine to reinforce and support future operations and to improve the road and rail infrastructure needed to move them rapidly around. They could optimize, in other words, for a short-notice attack at times and places of their choosing in ways that the ongoing combat now precludes.

No Space to Trade

Ukraine would need to defend right at the current lines in the event that Russia invades again following a period of reconstitution. Too many large population, industrial, and vital defensive centers are too close to the current lines for Ukraine to be able to trade space for time. Major urban areas with total pre-war populations of over five million (a bit over 11% of Ukraine’s total pre-war population) are within 160 kilometers (100 miles) of the current front lines. They include the vital population and industrial cities of Zaporizhzhia and Dnipro; Odesa and Mykolaiv, which are Ukraine’s sole remaining ports and essential to Ukraine’s ability to export its grain and other goods; and the cities of Slovyansk, Kramatorsk, and Kostyantynivka that are both populous and form Ukraine’s major eastern defensive bastion. Kharkiv remains a mere 32 kilometers from the Russian border but is now also threatened by Russian lines about 110 kilometers to the east and southeast.

A Ukrainian military seeking to deter or defeat a future Russian attack that begins on these lines will have to be fully manned and equipped and fight-tonight trained even in peacetime, as it will have no margin for error in almost any direction.

In a future invasion, Russian forces seeking to take Kherson, Mykolaiv, or Odesa will have to cross the Dnipro River—and do so without the benefit of the bridges they used in 2022. Those attacking further east or toward Kharkiv or Kyiv will confront prepared Ukrainian defensive fortifications. The Russians will, thus, face daunting challenges of their own, to be sure.

However, the aggressor benefits from many advantages in war. The Russians will be able to concentrate their own forces as close to the border as they like, along with all the air defense systems, bridging and other engineering equipment, artillery, ammunition, and other supplies they would need for a short-notice attack as noted above. The Ukrainians will not be able to attack those concentrations without breaking the ceasefire. The Russians can keep a sizable portion of their own troops in a constant (and expensive) state of mobilization and readiness if they choose, and Putin has shown a great degree of willingness to burn money (and lose Russian lives) in pursuit of his objectives. The Russians are currently challenged to sustain their mobilized military and the large losses it is taking in Ukraine while also attempting to mobilize their defense industrial base.[9] They can alleviate much of that pressure once the fighting stops, however, because they will no longer be taking losses, on the one hand, and will also be able to meter their defense industrial requirements at their own pace to be prepared for a renewed attack at a time of their choosing.

The Russians can also keep many of their assault forces in reserve, dispersed in training areas throughout Russia, bringing them to war readiness only at the intended moment of attack—at least, they will be able to do so if they can resolve the failures in their pre-2022 and current mobilization and training systems as they have set out to do.[10] The second approach would, of course, give Ukraine warning and the opportunity to mobilize its own reservists. But it would have to mobilize its reserves every time the Russians did in this configuration of the lines because it cannot afford to cede its frontline positions temporarily while mobilizing reserves to regain lost ground. That situation would give the Russians enormous control over the cost of money and social tension of deterring and defending against a Russian attack. The lines as they are now, in either case, would leave it to Putin and his successors to determine the financial and social cost Ukraine and its Western backers must bear for Ukraine’s continued survival, and that cost would likely be very high.

Crimea

The costs and challenges of Ukraine’s defense vary dramatically if Crimea returns to Ukraine or remains in Russia’s hands. The January 2022 lines considered above assume that Russia retains Crimea. If Ukraine liberates the peninsula along with Russian-occupied lines in the south, however, then the imminent threat to Kherson, Mykolaiv, and Odesa vanishes and the threat to Melitopol is dramatically reduced. Mariupol remains the only major front-line city in the south in this case, dramatically reducing the area of limited defensive depth and requiring high levels of prepared and partially- or fully-mobilized Ukrainian forces to defend. The liberation of Crimea also largely obviates the threat of Russian amphibious operations against the southwestern Ukrainian coast, as well as the Russian missile threat to ships attempting to transit the western Black Sea. Unfounded discussions of Russia’s “historic right” to Crimea, which Russia itself recognized as part of an independent Ukraine in 1994, obscure the high military and financial cost Ukraine and its backers will have to pay for as long as Russia occupies the peninsula.

Donbas

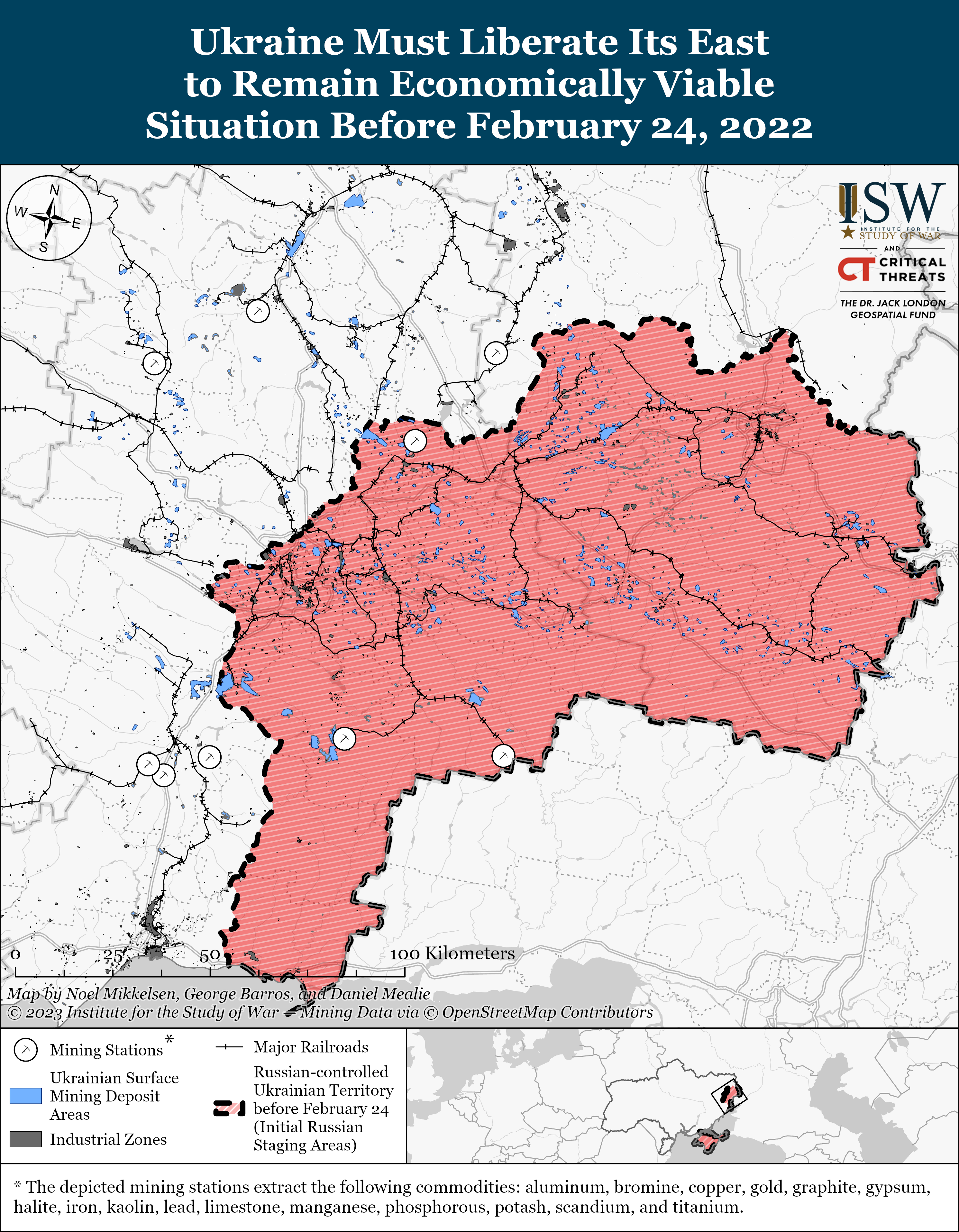

Ukraine’s liberation of pre-February 2022 occupied Donbas would not dramatically change the defensive military requirements for Ukraine, since Donetsk City and Luhansk City are so close to the Russian border themselves as to offer no meaningful defensive depth. It would, however, have enormous economic implications for Ukraine, which will be considered here only briefly. Donbas is one of Ukraine’s historic economic heartlands, home to Ukraine’s ore extraction and metallurgical industry. The 2014 line of control resulting from Russia’s first invasion of Ukraine actually divided that industry, separating mines from processing facilities and splitting the rail lines connecting them all. Ukraine did not feel anything like the full economic pain of that division, however, because by tacit agreement Moscow and Kyiv allowed the Ukrainian oligarch who controlled the region to continue to operate on both sides of the line of control.[11] That oligarch no longer controls these industrial assets, and it is almost impossible to imagine that a ceasefire that restored the January 2022 lines would include restoring Ukraine’s ability to benefit economically from its part of the entire industrial enterprise.[12] Accepting Russia’s permanent acquisition of eastern Donbas thus deprives Ukraine of considerable revenues, weakening its economy and increasing its economic and financial dependence on the West.

Conclusion

The most advantageous lines Ukraine could hold militarily and economically are its internationally recognized 1991 boundaries. Any discussion of recognizing changes to those borders as concessions to try to persuade Russia to stop its unprovoked and illegal invasion must reckon with the heavy blow such concessions would make against core principles of international law banning wars of conquest, ethnic cleansing, crimes against humanity, and many other moral and ethical principles that are central to a peaceful world. But discussions of such concessions are already underway, and so we have examined the concrete and pragmatic problems surrounding their implementation.

Freezing the Russian war in Ukraine on anything like the current lines enormously advantages Russia and increases the risks and costs to Ukraine and the West of deterring, let alone defeating, a future Russian attempt to fulfill Putin’s aims by force. The current lines are not a sensible starting point for negotiations with Russia even if Putin were serious about negotiating a ceasefire on those lines. They are, rather, the necessary starting point for the continued liberation of strategically- and economically vital Ukrainian lands, without which the objective of a free, independent, and secure Ukraine able to defend and pay for itself is likely impossible.

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/27/opinion/ukraine-military-aid.html; https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/23/world/europe/putin-russia-ukraine-war-cease-fire.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share&referringSource=articleShare

[2] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-19-2023; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-17-2023; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-14-2023; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-13-2023

[3] https://isw.pub/UkrWar120823; https://isw.pub/UkrWar120923

[4] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-30-2023; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-10-2023; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-november-16-2023; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-26-2023; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-13-2023

[5] https://ria dot ru/20231228/svo-1918691314.html; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-28-2023; https://t.me/medvedev_telegram/426; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-27-2023; https://t.me/medvedev_telegram/421; https://telegra dot ph/Intervyu-oficialnogo-predstavitelya-MID-Rossii-MVZaharovoj-francuzskomu-informagentstvu-AFP-12-09; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-13-2023; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-10-2023

[6] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russia%E2%80%99s-military-restructuring-and-expansion-hindered-ukraine-war ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar120323 ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar120223

[7] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukraine%E2%80%99s-operations-bakhmut-have-kept-russian-reserves-away-south

[8] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-october-12-2023 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-29-2023

[9] https://www.cnn.com/2023/12/12/politics/russia-troop-losses-us-intelligence-assessment/index.html ; https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/12/us/politics/russia-intelligence-assessment.html ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/high-price-losing-ukraine ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-december-29-2023

[10] https://isw.pub/UkrWar100623 ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar100523 ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar122323 ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar121923 ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-january-31-2023 ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-november-28 ;

[11] https://www.crisisgroup.org/europe-central-asia/eastern-europe/ukraine/261-peace-ukraine-iii-costs-war-donbas ; https://meduza dot io/feature/2016/03/25/hozyain-donbassa

[12] ; https://globalarbitrationreview.com/article/ukraines-richest-man-brings-treaty-claim-against-russia ; https://tass dot ru/ekonomika/17023511