|

|

The Russian Winter-Spring 2024 Offensive Operation on the Kharkiv-Luhansk Axis

The Russian Winter-Spring 2024 Offensive Operation on the Kharkiv-Luhansk Axis

Riley Bailey and Frederick W. Kagan with Nicole Wolkov and Christina Harward

February 21, 2024

Russian forces are conducting a cohesive multi-axis offensive operation in pursuit of an operationally significant objective for nearly the first time in over a year and a half of campaigning in Ukraine. The prospects of this offensive in the Kharkiv-Luhansk sector are far from clear, but its design and initial execution mark notable inflections in the Russian operational level approach. Russian efforts to seize relatively small cities and villages in eastern Ukraine since Spring 2022 have generally not secured operationally significant objectives, although these Russian operations led to large-scale fighting and significant Ukrainian and Russian losses.[1] Russian forces likely pursued more operationally significant objectives during their Winter-Spring 2023 offensive, but that effort was poorly designed and executed and its failure to make any substantial progress precludes drawing firm conclusions about its intended goals.[2] Russian offensives to this point have generally either concentrated large masses of troops against singular objectives (such as Bakhmut and Avdiivka) or else have consisted of multiple attacks along axes of advance that were too far away to be mutually supporting and/or divergent. The current Russian offensive in the Kharkiv-Luhansk sector, by contrast, involves attacks along four parallel axes that are mutually supporting in pursuit of multiple objectives that, taken together, would likely generate operationally significant gains. The design of this offensive operation is worth careful consideration regardless of its outcome as a possible example of the Russian command’s ability to learn from and improve on its previous failures at the operational level. Russian tactical performance in this sector, however, does not appear to have improved materially on previous Russian tactical shortcomings, a factor that may well lead to the overall failure even of this better-designed undertaking.

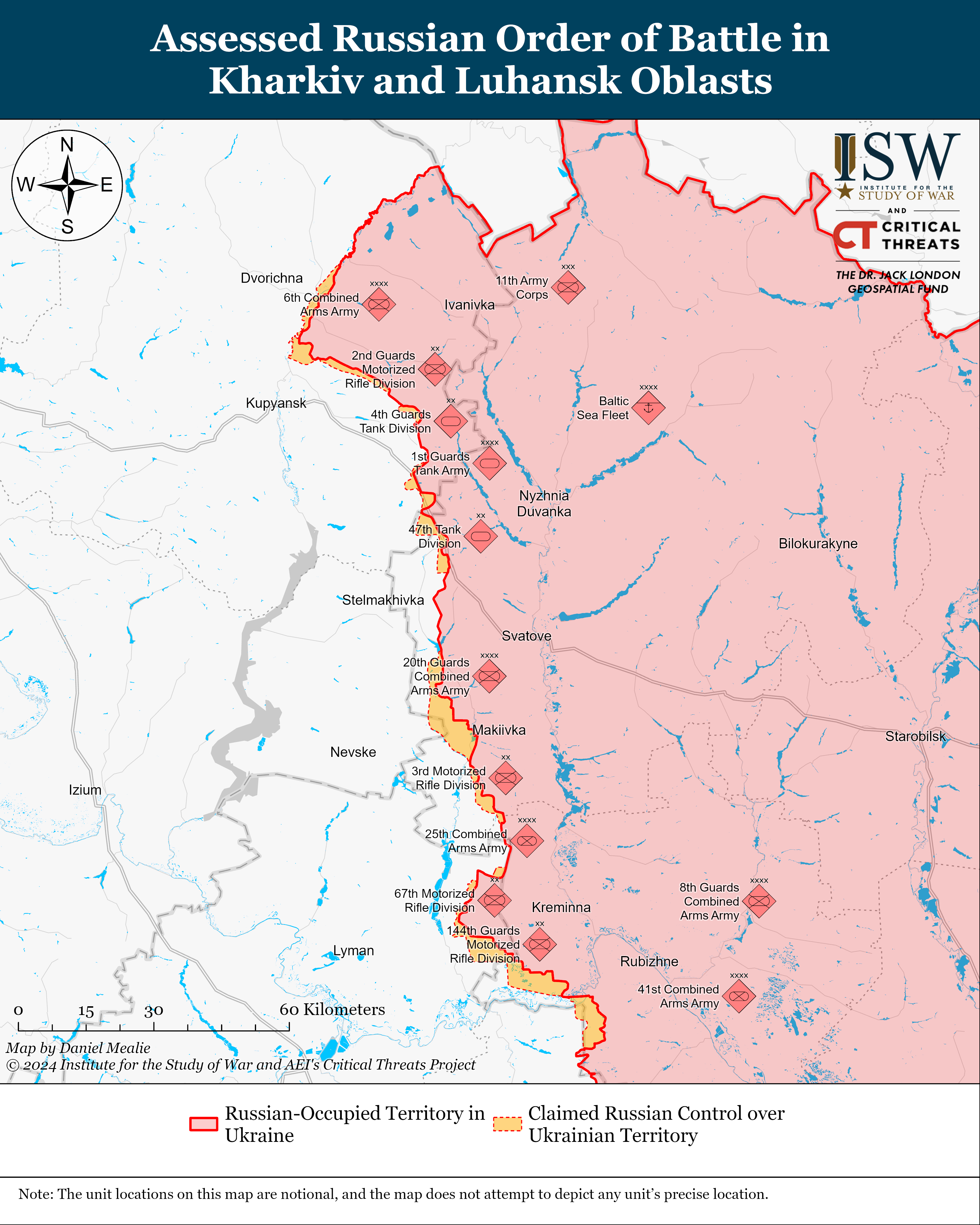

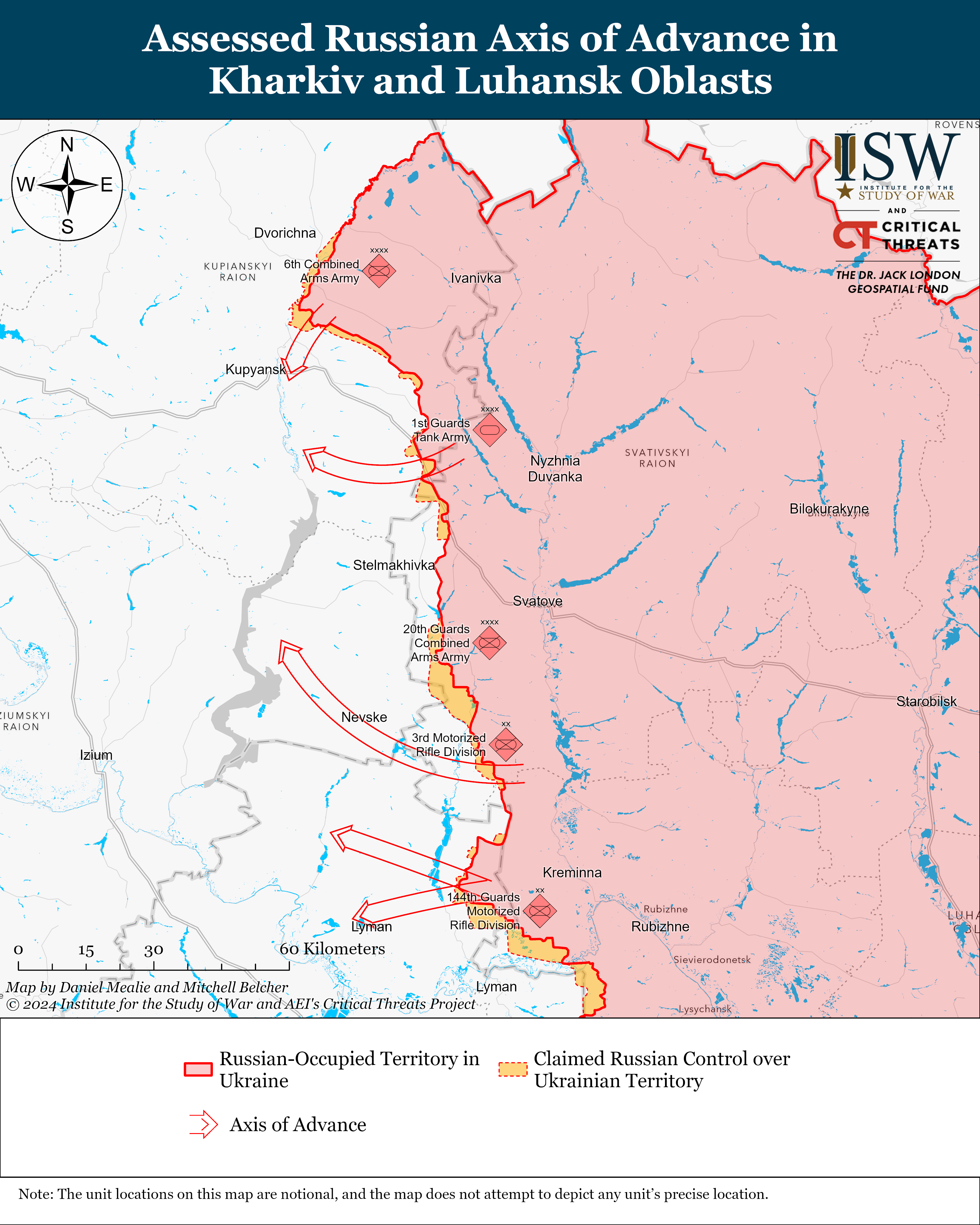

Russia’s Western Grouping of Forces has recently intensified operations along the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line and is focusing on four directions of advance. Russian forces are currently pursuing offensive operations northeast of Kupyansk, northwest of Svatove, southwest of Svatove, and west of Kreminna. The Russian Western Grouping of Forces (likely comprised almost entirely of elements of the Western Military District [WMD]) has had responsibility for much of the Kharkiv-Luhansk axis since the stabilization of the frontline following Ukraine’s successful counteroffensive in Kharkiv Oblast in fall 2022.[3] The Central Grouping of Forces (primarily comprised of elements of the Central Military District [CMD]) had responsibility for the southern portion of this axis in the Lyman direction between Fall 2022 and Fall 2023, but the WMD appears to have taken over responsibility for the northern portion of the Lyman direction after the Russian command transferred significant elements of the CMD to support the offensive effort to seize Avdiivka in Donetsk Oblast in early October 2023.[4] The WMD‘s 6th Combined Arms Army (CAA) and 1st Guards Tank Army (1st GTA) resumed a localized offensive effort northeast of Kupyansk on October 6, 2023 and sporadically intensified operations elsewhere in the Kupyansk direction.[5] This localized Russian offensive effort to advance towards Kupyansk from the northeast had resulted in only marginal tactical gains by January 2024, however. Ukrainian officials increasingly began to report in January 2024 that Russian forces were setting conditions for a larger offensive effort in both the Kupyansk and Lyman directions.[6] WMD elements began to intensify operations in four directions of advance along the line in early January, and Ukrainian Main Military Intelligence Directorate (GUR) head Lieutenant General Kyrylo Budanov announced by January 30 that the Russian 2024 winter-spring effort on the Kharkiv-Luhansk axis was underway.[7] The Russian offensive campaign is currently proceeding along four axes, from north to south: 1) around Kupyansk and Synkivka; 2) from Tabaivka toward Kruhlyakivka; 3) from Makiivka toward Raihorodka and/or Borova; and 4) from near Kreminna to Drobysheve and/or Lyman.

Kupyansk-Synkivka Axis

Elements of the 6th CAA are currently conducting offensive operations northeast of Kupyansk near Synkivka in an ongoing effort to advance towards east bank Kupyansk. Elements of the 6th CAA and 1st GTA began a localized offensive operation to push towards east bank Kupyansk and northern Kupyansk Vuzlovy in October 2023 that primarily focused on areas surrounding Synkivka as well as Vilshana and Petropavlivka.[8] Russian aviation supported this effort by conducting a series of strikes on bridges crossing the Oskil River from September through October 2023 that likely aimed to isolate the Ukrainian defenses northeast of Kupyansk while also setting conditions for the current wider Russian offensive operation.[9] Synkivka is located along a railway line and a road leading into Kupyansk and Kupyansk Vuzlovy, and Ukrainian military officials have identified the Synkivka area as providing the most rapid route for Russian forces to reach the two settlements on the east bank of the Oskil River.[10] Likely elements of the 6th CAA’s 25th Motorized Rifle Brigade and 128 Motorized Rifle Brigade conducted relatively large company-sized mechanized assaults in the Synkivka area in December 2023 that resulted in significant Russian armored vehicle losses and no notable tactical gains, and Russian forces have since heavily relied on infantry assaults with limited armored vehicle support in the area.[11] Elements of the Russian 25th Motorized Rifle Brigade are currently conducting assaults on Synkivka, and elements of the 128th Motorized Rifle Brigade are reportedly operating in the Vilshana area.[12] Russian forces have reportedly made tactical gains in the Synkivka area in intensified assaults in late January, although ISW has not seen confirmation of any recent notable tactical gains near the settlement.[13] Ukrainian officials continue to assess that Russian assaults near Synkivka aim to facilitate Russian advances to Kupyansk and Kupyansk-Vuzlovy, where there are two bridges crossings over the Oskil River.[14]

Elements of the 1st GTA are reportedly still operating near Synkivka, although it is unclear if they are conducting assaults in the area.[15] Elements of the 1st GTA’s 2nd Motorized Rifle Division reportedly conducted attacks near Orlyanka (east of Kupyansk) in early January 2024, although it is unclear if some of these elements are still in the area.[16] Elements of the 2nd Motorized Rifle Division participated in offensive efforts near Stepova Novoselivka (south of Orlyanka) in early February 2024 suggesting that they may have shifted their focus to the Russian effort further south.[17]

Tabaivka-Kruhlyakivka Axis

Elements of the 1st Guards Tank Army, primarily its 47th Tank Division, have intensified operations northwest of Svatove, have recently made tactical gains around Tabaivka, and appear to be pushing west toward the Oskil Reservoir in the direction of Kruhlyakivka and northwest along the P07 highway toward Kupyansk-Vuzlovy. Russian forces intensified operations northwest of Svatove in January 2024 more than anywhere else along the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line. Elements of the 47th Tank Division began what Russian sources described as a “massive offensive” in the direction of Krokhmalne and Tabaivka on January 19.[18] Geolocated footage published on January 20 indicated that Russian forces had quickly captured Krokhmalne, and elements of the 47th Tank Division reportedly captured Tabaivka as early as January 27, although ISW has still not observed confirmation of Russian forces capturing the settlement as of February 20.[19] Russian sources claimed that Russian forces also entered Ivanivka (north of Tabaivka) and advanced closer to Kyslivka (immediately north of Tabaivka) as of February 1.[20] Russian sources have claimed that Russian forces may have captured Kotlyarivka (immediately north of Tabaivka), and elements of the 27th Motorized Rifle Brigade (1st GTA) have reportedly advanced near Berestove (just south of Krokhmalne).[21] Russian forces have also resumed assaults near Stelmakhivka (south of Krokhmalne) and near Pishchane (immediately southwest of Tabaivka).[22]

Elements of the 2nd Motorized Rifle Division's 1st Tank Regiment and 15th Motorized Rifle Regiment unsuccessfully attempted to encircle Ukrainian forces near Stepova Novoselivka (north of Kyslivka) in early February as elements of the 4th Tank Division (1st GTA) reportedly tried to push through Ukrainian defenses near Kyslivka.[23] Elements of the 47th Tank Division appear to be the main force committed to the effort northwest of Svatove, but the participation of elements of the 27th Motorized Rifle Brigade, the 2nd Motorized Rifle Division, and the 4th Tank Division in offensive operations in the area suggests that the wider 1st GTA is responsible for offensive operations this area of the line and is not actively committed to the effort northeast of Kupyansk.

Russian operations around Tabaivka appear to be pushing along diverging axes to the northwest and west-southwest, and it is not yet clear which is the main effort. Russian milbloggers claimed that Russian forces are currently developing an offensive in the direction of Pishchane from Tabaivka in an effort to reach the Oskil River.[24] Pishchane and Berestove are located along a country road connecting the P07 highway to Kruhlyakivka, where one of the six bridges crossing the Oskil River is located. There is also a country road that begins west of Kyslivka and Kotlyarivka and connects the P07 highway to Kurylivka and southern Kupyansk-Vuzlovy, where a railway and roadway bridge across the Oskil River are located. The Russian tactical effort to seize settlements along the P07 highway likely aims to open routes of advance for Russian forces to reach Kurylivka, southern Kupyansk Vuzlovy, and Kruhlyakivka and threaten Ukrainian ground lines of communication (GLOCs) connecting the east and west banks of the Oskil River in the area.

Makiivka/Raihorodka-Borova Axis:

Elements of the 20th CAA’s 3rd Motorized Rifle Division are attacking southwest of Svatove, although they are currently conducting a lower tempo of operations in the area than Russian forces elsewhere along the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line. Russian forces attacked southwest of Svatove, particularly near Makiivka on the Zherebets River, in January 2024, although at a slower tempo than other areas along the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line.[25] Geolocated footage published on January 27 indicates that Russian forces have recently advanced east of Makiivka, and elements of the 20th CAA’s 3rd Motorized Rifle Division have reportedly recently increased efforts to advance near the settlement.[26] Ukrainian and Russian sources reported positional engagements in the area throughout January 2024.[27] Russian and Ukrainian sources also stated that Russian forces conducted offensive operations near Makiivka throughout December 2023, but ISW did not observe visual confirmation of any Russian advances in the area during this time.[28]

Russian forces consisting mostly of elements of the 2nd CAA (CMD) previously conducted offensive operations southwest of Svatove along the Raihorodka-Karmazynivka-Novovodyane line further north of Makiivka in the summer and early fall of 2023, with Ukrainian Commander-in-Chief Colonel General Oleksandr Syrskyi stating in August 2023 that the Raihorodka area was one of the most intense sectors of the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line.[29] ISW has not observed reports of the CMD’s 2nd CAA operating southwest of Svatove in 2024, however, suggesting that the transfer of elements of the CMD‘s 2nd CAA from the area and subsequent transfer of elements of the WMD’s 20th CAA may be part of an effort to cohere a large effort around WMD forces along the entire Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line.

Ukrainian Khortytsia Group of Forces Spokesperson Captain Ilya Yevlash stated the Russian forces intended to reach Borova before the start of winter 2023-2024 during localized Russian offensive operations in the area in early Fall 2023.[30] The CMD forces failed to achieve that goal, but there is no reason to assess that WMD elements in the area have shifted their goal away from Borova. Makiivka and Raihorodka are located on country roads that connect the P66 Svatove-Kreminna highway to Borova where there is a crossing over the Oskil River. The route from Raihorodka to Borova, however, is more direct than the route from Makiivka to Borova, suggesting that Russian forces may choose to resume offensive operations near Raihorodka aimed at advancing to Borova. Alternatively, country roads from Makiivka lead southeastward to Lyman, and current Russian activity near Makiivka could additionally be aimed at supporting offensive efforts to cross the Zherebets River west of Kreminna. Country roads from Makiivka also lead to several settlements south of Borova along the Oskil River and Oskil City, and Russian efforts near Makiivka may be ultimately aimed at securing the southern edge of the Oskil Reservoir (before it narrows at the Oskil Hydroelectric Power Plant).

Kreminna-Drobysheve/Lyman Axis

Elements of the 20th CAA’s 144th Motorized Rifle Division have intensified an effort to push Ukrainian forces off the left bank of the Zherebets River west of Kreminna while non-WMD elements continue routine positional fighting elsewhere in the Lyman direction.[31] Russian and Ukrainian sources have stated that elements of the 144th Motorized Rifle Division were pursuing this effort as early as November 2023, although ISW did not observe a concerted offensive effort to push towards the Zherebets River until early January 2024.[32] Likely elements of the 144th Motorized Rifle Division notably intensified this effort around January 20 with reports of Russian forces using a significant number of tanks, BMPs, and armored vehicles in a relatively large number of assaults in the area.[33] Geolocated footage published on January 21 showed at least 20 new Russian vehicle losses following unsuccessful assaults near Terny (west of Kreminna).[34] The most recent intensified Russian assaults have focused on Terny, Yampolivka, and Torske — three settlements on the Zherebets River with nearby crossings — and Russian forces have made recent minor marginal tactical gains in the area.[35] Russian milbloggers have claimed that Russian forces have advanced close to the outskirts of Torske, although ISW has yet to observe confirmation of these claims.[36] Russian forces have advanced within two kilometers of the eastern outskirts of Terny as of February 12.[37]

Elements of the newly created 25th CAA (CMD) have also conducted localized offensive operations in the area since October 2023, and elements of the 25th CAA’s 164th Motorized Rifle Brigade are reportedly supporting the 144th Motorized Rifle Division’s current efforts near Yampolivka.[38] Elements of the 25th CAA’s 169th Motorized Rifle Brigade are reportedly operating southwest of Kreminna with other elements of the 144th Motorized Rifle Division.[39] It is unclear how involved the 25th CAA is in the 144th Motorized Rifle Division's intensification of offensive operations in the northern portion of the Lyman direction or if the Russian command intends for these elements to stabilize the surrounding frontline as the 144th Motorized Rifle Division continues its push towards and across the Zherebets River.

Elements of the 90th Tank Regiment (41st CAA, CMD) were reportedly participating in positional engagements southwest of Kreminna in December 2023, but ISW has not observed indications that the 90th Tank Regiment or other CMD elements except the 25th CAA are currently committed to the Russian offensive effort in the Lyman direction.[40] Significant portions of the CMD’s 41st CAA and 2nd CAA transferred from the Lyman direction to the Avdiivka direction around early October 2023 and participated in the completion of the seizure of Avdiivka.[41] Elements of the 90th Tank Division‘s 80th and 239th Tank Regiments are currently operating near Avdiivka, although other elements may still remain in the Kreminna area.[42] It is unclear what elements of the CMD may still be deployed in rear areas of occupied Luhansk Oblast, although any remaining elements likely represent only a fraction of the combat power that the CMD had previously deployed in the area.

Luhansk People’s Republic (LNR) 2nd Army Corps (AC) elements and Chechen Akhmat Spetsnaz forces are operating around Kreminna and have reportedly intensified operations south of Kreminna, but are likely not directly participating in the concerted Russian effort in the Lyman direction.[43] Russian milbloggers have claimed that Russian forces intensified offensive operations near Bilohorivka (12km south of Kreminna) in mid-January 2024 and have made tactical advances in the area, although ISW did not observe evidence of any Russian advances in the area until early February and has not observed a significant intensification of the tempo of Russian operations near Bilohorivka.[44] LNR 2nd AC and Akhmat Spetsnaz elements are likely engaged in tactical efforts that have little relevance to the wider operational effort in the Lyman direction.

Reaching the Zherebets River and pushing Ukrainian forces across to the right bank of the river is only an immediate tactical objective, and Russian forces likely have more ambitious subsequent operational objectives in the area. Russian forces may have attempted to recapture Lyman, Donetsk Oblast during the failed Russian Winter-Spring 2023 offensive campaign in Luhansk Oblast, although the Russian failure to make any meaningful advances makes determining the ultimate objective of the offensive difficult.[45] Recapturing Lyman is the most likely operational objective for Russian forces in the area as the settlement opens routes of Russian advance both to the northwest towards Oskil City (southeast of Izyum) and to the southwest towards Slovyansk. Russian forces may alternatively intend to advance north of Lyman towards Drobysheve in an effort to support planned advances towards the Oskil River and set conditions for the later seizure of Lyman.

Russian Operational Planning and Objectives

The apparent coordination of Russian offensive efforts along the four axes on the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line is likely reflective of a wider operational objective and higher-level operational planning. Russian objectives in each direction of advance appear to add up to a wider cohesive operational objective to seize the east bank of the Oskil River in Kharkiv Oblast. Russian operations on each axis share similarities in design and support one another in ways that suggest that the command of the Russian Western Grouping of Forces has planned a larger operation in pursuit of this cohesive operational objective.

Objectives

These four directions of Russian advance along the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line and the apparent Russian objectives in those directions suggest that the Russian Western Grouping of Forces is undertaking a larger months-long cohesive operational effort to seize the east bank of the Oskil River from Kupyansk to Oskil City. The fact that these directions of advance all fall under the operational responsibility of a cohesive Russian grouping of forces suggests that the Russian command has tasked the Western Grouping of Forces to pursue a coordinated operational objective on the Kharkiv-Luhansk axis. The clear delineation of those directions among elements of the 6th CAA, the 1st GTA, the 20th CAA’s 3rd Motorized Rifle Division, and the 20th CAA’s 144th Motorized Rifle Division suggests that the Western Grouping of Forces deployed relatively cohesive formations in distinct areas of operation well in advance of this effort. The intensification of Russian offensive operations along these axes of advance at the same time suggests that this activity is part of a wider operation and not four separate localized offensive efforts. The likely planned Russian objectives of advancing to and seizing east bank Kupyansk, Kupyansk-Vuzlovy, Kurylivka, Kruhlyakivka, Borova, settlements south of Borova, and areas near or north of Lyman would all support a coordinated objective of pushing Ukrainian forces off the east bank of the Oskil River in Kharkiv Oblast. Russian advances to and the seizure of these settlements would otherwise only have limited tactical significance.

An operation to push Ukrainian forces off the east bank of the Oskil River offers the Russian military an attainable goal that would generate operationally significant effects. The seizure of east bank Kupyansk, Kupyansk-Vuzlovy, Kurylivka, Kruhlyakivka, Borova, settlements south of Borova, and areas near or north of Lyman as well as corresponding areas where there are river crossings would likely create conditions that would make continued Ukrainian operations on the east bank of the Oskil River untenable. This operation would also allow Russian forces to safely consolidate after the offensive’s planned culmination as there would be little risk of serious Ukrainian counterattacks back across the river. It would be surprising if the Russian command did not plan this operation with this relatively attainable objective and favorable conditions for consolidation but rather chose a less cohesive, less favorable, and less attainable effort--but Russian commanders have made similarly poor choices repeatedly throughout the war.[46]

The Kremlin has often prioritized military efforts to achieve informational or political objectives over those with wider operational significance in Ukraine, but an operation to reach the Oskil River offers Russia opportunities for both kinds of gains.[47] Ukrainian military officials have noted that Russian forces may be intensifying offensive operations to take territory ahead of Russia’s March 2024 presidential elections, suggesting that Russian President Vladimir Putin intends to secure an informational victory in Ukraine to bolster his reputation as a capable war-time leader amid his certain re-election.[48] Operations northwest of Svatove, southwest of Svatove, and near Kreminna offer the Russian military the opportunity to seize the remainder of unoccupied Luhansk Oblast, and the Kremlin has long pursued the seizure of all of Luhansk Oblast as one of its main objectives in eastern Ukraine.[49] The more operationally significant effort to reach the Oskil River would achieve this informational objective and more. But seizing the remainder of Luhansk Oblast could still be an attainable objective even if the wider operation fails since Ukrainian forces only control a small sliver of Luhansk Oblast south of Kreminna and west and southwest of Svatove. The seizure of all of Luhansk Oblast may be a subordinate objective, but three of the axes of the Russian offensive effort are focused on territory in Kharkiv and Donetsk oblasts, suggesting that the primary objective is reaching the Oskil River and possibly taking Kupyansk. The Kremlin could settle for this secondary objective for its informational benefits, but only if it appears unable to achieve its primary goals.

The Western Grouping of Forces appears to be conducting the initial stages of an intensified cohesive offensive operation to reach the Oskil River on a broad front, but the Russian command could decide to pursue other objectives that diverge from this cohesive effort. Potential Russian advances towards Lyman would divert Russian forces along diverging axes of advance towards separate operational objectives that are not necessarily mutually supporting. The Russian command could decide to break the Lyman effort off from the overall operation to reach the Oskil River if the wider operation makes little progress or if the capture of Lyman and advances south of the settlement look more attractive than trying to advance all the way towards Oskil City. The terrain south of Lyman would likely be less favorable to Russian advances, however. Lyman also offers a less attractive position either to consolidate gains or to resume subsequent attacks because of the forest belts around it and the open flanks it would offer to Ukrainian counterattacks. Lyman’s position on a seam between groupings of forces would also pose greater command and control challenges to Russian efforts to consolidate and defend or exploit its seizure.

Planning

Russian forces appear to be attacking along mutually supporting axes, something Russian forces have often failed to do in the past, which suggests possible improvements in Russian operational planning at least in this sector of the front.[50] The areas in which Russian forces are trying to advance are mutually supporting because they are roughly parallel with one another and close enough together to generate pressure on the same groupings of Ukrainian defenders. The flank of one direction of advance is close enough to the flank of the adjacent direction to create synergistic effects. For example, a Russian tactical advance northwest of Svatove could also be seen as a tactical advance on the northern flank of the Russian effort west and southwest of Svatove or as an advance on the southern flank of the effort northeast and east of Kupyansk. A Russian advance in one of these directions places pressure not just on the Ukrainian forces defending in the immediate tactical area but also on Ukrainian forces that are defending against Russian offensive operations north or south of the direction in which Russian forces advanced.

Mutually supporting operations also set conditions for the tactical envelopment or encirclement of Ukrainian forces in some areas if Russian forces can advance rapidly enough or if Ukrainian defenders make mistakes. Many of the settlements along the Oskil River that Russian forces are apparently trying to capture can be reached by forces advancing along adjacent axes, which could allow Russian forces to envelop or encircle a settlement instead of attacking it frontally. Russian forces can approach northern Kupyansk-Vuzlovy by advancing from Synkivka and can approach southern Kupyansk Vuzlovy from the direction of advance northwest of Svatove, for example. Similarly, the Russian advances towards Kruhlyakiva from settlements along the PO7 highway northwest of Svatove and advances southwest of Svatove from Makiivka can set conditions for Russian forces to envelop or encircle Ukrainian forces defending Borova. The four mutually supporting directions present Russian forces with opportunities to envelop or encircle east bank Kupyansk, Kupyansk-Vuzlovy, Kurylivka, Kruhlyakivka, and Borova depending on the rate and timing of Russian advances. The mutually supporting operations do not provide these opportunities for areas near or north of Lyman, however, as Lyman is on the flank of the overall operational effort along the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line.

The likely Russian offensive operation towards the Oskil River appears to be a much more sustainable effort than previous Russian offensive operations in Ukraine. The following observations are based on the current tempo of Russian offensive operations along the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line, and it is unclear if many of them would hold in the event of a significant intensification of the Russian offensive effort. Ukrainian artillery shortages and delays in Western security assistance are creating uncertainty in Ukrainian operational planning and are likely prompting Ukrainian forces to husband materiel.[51] These constraints on Ukrainian operations are likely limiting Ukraine’s ability to degrade and pressure Russian forces and logistics along the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line, and it is unclear if the Russian military would be able to conduct a relatively sustainable offensive operation in the absence of these Ukrainian constraints.

Russian forces attacking along the Luhansk-Kharkiv axis appear to be attempting to use some of the principles of Soviet deep battle theory, particularly the principle of conducting multiple simultaneous attacks to pin the defender’s frontline forces and reserves.[52] Russian forces have shown a pattern of activity along the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line that suggests that Russian forces are alternating intensified attacks along certain axes with regrouping and consolidation along others. Russian forces have alternated their intensified tactical activity in January 2024 among their four axes of advance and have only occasionally significantly intensified offensive operations in two directions at the exact same time.[53] Russian forces conducted routine regroupings during their localized offensive operation northeast of Kupyansk between October 2023 and January 2024 that likely allowed them to sustain that effort despite manpower and equipment losses.[54] Russian forces likely intend to alternate the intensity of operations along the four axes of advance in a staggered manner in order to allow Russian forces in each direction to similarly periodically regroup and prepare for future assaults. This rotating intensification throughout the frontline likely aims to maintain pressure on Ukrainian defenders all along the east bank of the Oskil River even as some Russian groupings regroup and reconstitute. This approach likely also aims to prevent Ukrainian forces from concentrating on a single Russian axis of advance. This rotating intensification pressures the entire Ukrainian force grouping defending in the area and complicates Ukraine’s ability to transfer forces between different defensive directions.

The current tempo of Russian offensives along the Kharkiv-Luhansk axis, Russian force generation efforts, and the Russian ability to conduct operational-level rotations will likely allow Russian forces to conduct offensive operations along each axis of advance without pulling manpower away from another. The tempo of Russian offensive operations in Ukraine is generating personnel losses at a rate roughly equal to the rate at which Russia is currently generating new forces through crypto-mobilization efforts.[55] Ukrainian military officials have noted that Russian forces in the Kupyansk and Lyman directions routinely make good their losses during periods of decreased offensive activity and regroupings.[56] The reported concentration of the Russian military’s entire combat-capable ground force in Ukraine and the fact that Russia appears to be able to replace losses on a one-to-one basis across the theater allows Russian forces to conduct routine operational level rotations throughout the theater.[57] The ability to conduct rotations in principle allows Russian forces to mitigate the degradation of attacking Russian forces that over time could cause Russian offensive efforts to culminate, thereby making Russian offensive efforts at current levels of intensity sustainable.[58]

The losses Russian forces have taken in their effort to seize Avdiivka prompted the Russian command to transfer elements from other sectors of the front to support that effort, but the Russian elements attacking along the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line are doing so in a way that has not thus far required the commitment of reserves from other sectors of the front.[59] The 6th CAA, the 1st GTA, the 20th CAA’s 3rd Motorized Rifle Division, and the 20th CAA’s 144th Motorized Rifle Division will likely be able to continue to replenish their losses and rotate degraded units at the current operational tempo without drawing on Russian reserves from other formations. The Russian military is replenishing losses with poorly trained and relatively combat ineffective personnel, however, and despite rotations and replenishment, losses over time will likely degrade the combat effectiveness of the attacking WMD elements and hinder their ability to sustain effective offensive operations.[60] The Russian offensive effort toward the Oskil River will thus likely culminate at or before the river line, and the Russians will likely have to conduct a fundamental reconstitution of the formations involved in this offensive before using them in subsequent major offensive operations.

The apparent Russian ability to conduct routine regroupings and resume offensive operations on individual axes without drawing combat power from other axes is letting Russian forces sustain operations on each axis at their own pace. The degradation of Russian forces on one axis does not appear to influence the tempo of operations on other axes along the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line. Russian forces on a given axis could even potentially culminate short of the river line without fully disrupting the overall operational scheme. The limited number of crossings and the vulnerability of those crossings to Russian fires also mitigates the risks caused by the premature culmination of a given axis—Ukrainian forces could be driven to withdraw from the entire east bank by the threat of being cut off even if they manage to stop one or more axes of Russian advance short of the river. This situation would likely not hold, however, if the Ukrainian forces managed to block one or more of the Russian advances in such a fashion that the Russian command had to divert effort from another axis to sustain its coherent drive.

The apparent sustainability of the Russian offensive effort and the mutually reinforcing directions of Russian advance suggests that the Russian command may be learning from previous operational design failures. Russian forces have previously conducted offensive operations at tempos far beyond their ability to replace losses in manpower and materiel.[61] The tempo of Russian offensive operations during the Russian Winter-Spring 2023 offensive campaign and the Wagner’s Group concerted offensive to capture Bakhmut both required Russian forces to expend manpower and materiel at an unsustainable rate.[62] Those offensives both culminated prematurely--the Winter-Spring 2023 campaign achieved virtually no gains. The Wagner offensive ultimately took Bakhmut, but did so in a way that left Russian forces unprepared to defend against Ukrainian counterattacks and required the deployment of significant Russian reserves drawn from elsewhere in the theater to hold most of the gains made.[63] The seizure of Bakhmut combined with the Wagner Group‘s abortive armed rebellion also led to the effective destruction of the Wagner Group as a fighting force. The apparent relatively sustainable operation to reach the Oskil River is notable in this context and suggests that the Western Grouping of Forces has intentionally designed operations to avoid a premature culmination of its ongoing effort. Russian forces have also routinely attacked along diverging axes throughout the Russian invasion of Ukraine, an approach that has regularly prevented Russian forces from capitalizing on tactical gains and translating them into operationally significant [64] The Western Grouping of Forces appears to be learning from this mistake as well.

The Southern Military District’s [SMD] 58th CAA proved during its defensive effort in western Zaporizhia Oblast against the Ukrainian summer 2023 counteroffensive that at least some Russian formations can internalize lessons learned and successfully adapt campaign designs and tactical preparations to the battlefield realities in Ukraine.[65] ISW has yet to observe a Russian formation demonstrate this adaptation for operational planning at scale while conducting an offensive operational effort, and recent waves of mass mechanized assault around Avdiivka in October and November 2023 suggested that the Russian command has not disseminated tactical lessons learned from previous failed Russian offensive efforts.[66] The Western Grouping of Forces‘ current offensive operation may be the first instance of a large formation capturing and implementing at least campaign design lessons. Russian offensives along the Oskil River have not shown tactical improvements or innovations, however. Russian tactical engagements continue to display many of the same mistakes Russian offensive operations have repeatedly shown, causing high losses of men and materiel for limited gains. Russian learning and innovation thus appear to be partial and possibly confined thus far to operational level planning and force generation.

Prospects of the Russian Offensive Operation on the Kharkiv-Luhansk Axis

Russian forces will likely struggle to translate minor tactical advances into operationally significant maneuver towards the Oskil River, and the effort will likely take months of campaigning regardless of its ultimate success or failure if Ukrainian forces retain the material capability to continue resisting as they have. Russian forces have not learned how to restore mechanized maneuver to the positional battlefield in Ukraine and have not conducted any offensive operation that has resulted in a rapid mechanized advance since spring 2022.[67] A successful Russian advance to the Oskil River would very likely result from months of accumulated marginal tactical Russian gains at very high cost.

Rate of Advance and Types of Maneuvers

Russian forces are very unlikely to advance fast enough to encircle sizable pockets of Ukrainian forces. The likely gradual rate of Russian advance will allow Ukrainian forces to prepare positions, deployments, and logistics around settlements on the east bank of the Oskil River well ahead of any potential Russian advance towards these settlements. A threatened Russian encirclement of Ukrainian forces in these settlements rapid enough to prompt Ukrainian forces to withdraw to the west bank of the Oskil River is highly unlikely. The gradual rate of Russian advance will thus likely culminate in attritional frontal attacks against entrenched Ukrainian positions in and near settlements along the Oskil River before the final Ukrainian forces withdraw.

Russian forces have previously struggled to conduct significant operational encirclements and likely will continue to do so even if they can gradually envelop settlements along the Oskil River. Russian forces failed to operationally encircle Bakhmut in March 2023 and proceeded to fight through the city for two months in highly attritional assaults.[68] Russian forces have also failed more recently to operationally encircle smaller settlements such as Marinka and Avdiivka, although the threat of a tactical Russian encirclement forced Ukrainian forces to withdraw from Avdiivka on February 16.[69] Russian forces can advance in areas north and south of settlements along the east bank of the Oskil River and may envelop Ukrainian forces but Russian forces are very unlikely to complete operational encirclements. The fact that these settlements are backed up against a water feature may give Russian forces a better chance to trap Ukrainian forces against the river (effectively an encirclement), but only if the Russians can advance more rapidly than they have generally been able to do or if the Ukrainians either choose to defend a settlement to the last or make a mistake in timing their withdrawal. Russian forces will likely have to conduct assaults into and through east bank Kupyansk, Kupyansk Vuzlovy, Kurylivka, Kruhlyakivka, and Borova if they wish to capture these settlements. Russian offensive operations to capture even relatively small settlements with entrenched Ukrainian positions have lasted months, and in some cases years, and there is no reason to assess that fighting into and through these relatively small settlements will be much easier for Russian forces as long as Ukrainian forces have the materiel needed to continue defensive operations effectively.

Russian interdiction efforts will likely have greater chances of isolating the battlespace on the east bank of the Oskil River than elsewhere in Ukraine where Russian forces are conducting offensive operations, however. Six bridges (both railway and roadway bridges) cross the Oskil River between Kupyansk and the Oskil Hydroelectric Power Plant. Satellite imagery from mid-January suggests that many of these bridges have sustained some damage and a few appear unlikely to be usable by heavy equipment.[70] Russian forces likely damaged these bridges during a coordinated strike campaign on crossings along the Oskil River in September and October 2023, although this effort did not isolate the Ukrainian defense northeast of Kupyansk, and Ukrainian forces have not yet shown any signs of suffering from serious difficulties in supplying positions on the east bank of the Oskil River.[71] Russian forces may resume this effort to degrade Ukrainian logistics and force Ukrainian forces to transfer heavy equipment across the river with more vulnerable crossing equipment. Russian forces may also hope that advances closer to the Oskil River will allow Russian fire to interdict the Ukrainian GLOCs running along the west bank of the Oskil River (especially the P-79 and P-78 highways). Russian forces may envision conducting an interdiction effort that eliminates existing Ukrainian crossings to the east bank while also degrading logistics supporting areas on the west bank from where Ukrainian forces could deploy new crossings. The Russian command likely hopes that the isolation of the battlespace will allow Russian forces to conduct the operational encirclements and envelopments that they have previously failed to conduct.

Elements of the Russian Western Grouping of Forces, particularly of the 1st GTA, began this operation less degraded and better rested than Russian forces elsewhere along the frontline, which may allow these elements to conduct more effective offensive operations than other Russian force groupings. Russian forces have likely gradually reconstituted units of the 1st GTA through partial mobilization in September 2022 and subsequent crypto-mobilization following their severe degradation during the Ukrainian September 2022 counteroffensive and Russia’s failed winter-spring 2023 offensive.[72] ISW assessed that Russian forces operating in the Kupyansk direction likely do not need to reconstitute their kit to full doctrinal end strength as Russian forces rely on dismounted infantry assaults to conduct consistent assaults while conserving armored vehicles for periodic mechanized assaults in this direction.[73]

These elements may not necessarily have the combat capabilities required to conduct successful maneuver to the Oskil River line, however. A prominent Kremlin-affiliated Russian milblogger questioned the Russian Western Grouping of Forces’ ability to conduct successful offensive operations in the Kupyansk direction after footage published in late December 2023 showed Ukrainian artillery, drones, and an armored vehicle easily repelling a Russian infantry assault with armored vehicle support columns near Synkivka.[74] The milblogger claimed that the Western Grouping of Forces is ”incompetent” and suffers from ”systemic problems” and conducts infantry-led frontal assaults that lack sufficient artillery support.[75] The milblogger compared the failed Russian assault near Synkivka to the Russian failure to learn after the heavily attritional Russian attacks near Vuhledar in 2023 and the failed Siverskyi Donets River crossing near Bilohorivka in 2022, in which Ukrainian forces destroyed columns of Russian armored vehicles.[76]

The manpower fill and combat-effectiveness of the newly formed 25th CAA may affect the Russian military’s ability to conduct and support successful offensive operations west of Kreminna where the formation is operating. Ukrainian Main Military Intelligence Directorate (GUR) Head Kyrylo Budanov stated in late August 2023 that Russian forces formed the 25th CAA as a “strategic reserve” and did not intend the formation to be combat ready before October or November 2023.[77] Budanov also stated that elements of the 25th CAA deployed to Luhansk Oblast in late August 2023 and were poorly trained and staffed with 80 percent of their planned manpower and only 50 percent of the necessary equipment, likely due to their rushed deployment.[78] The likely limited combat power of the 25th CAA may affect the Russian military‘s ability to hold positions near Kreminna as the 144th Motorized Rifle Division pursues advances toward the Zherebets River.

Advances towards the Oskil River will likely require successful mechanized maneuver in many places, and Russian forces remain unlikely to be able to conduct such maneuver across the entire Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line. Many of the areas where Russian forces are currently attacking are heavily forested, flanked by forested areas, or dotted with windbreaks, particularly near Synkikva and Kreminna. Ukrainian military personnel have previously noted that Russian forces take advantage of this terrain to provide cover for infantry heavy assaults.[79] The land further west of the frontline in the direction of the Oskil River, particularly northwest of Svatove, is far more open. Russian advances through this terrain will likely require at least some successful mechanized assaults while under Ukrainian fire with high visibility. Recent chaotic and costly Russian mechanized assaults throughout the theater, including along the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line, suggest that WMD elements will struggle to advance in these areas and that assaults will likely produce significant armored vehicle losses that slow and disrupt the offensive operations.[80] Russian forces have proven more capable of making marginal tactical gains in urban or semi-urban environments, although at the expense of heavy personnel losses, as seen with the seizure of Bakhmut and Avdiivka.[81] Russian forces throughout much of the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line would have to advance roughly between eight and 35 kilometers through rural and open terrain to reach such semi-urban areas.

Wider Operational Considerations

The Kremlin may believe that delayed Western security assistance to Ukraine will give Russian forces opportunities to accelerate advances in the coming months, although it is unclear if this belief is accurate. Russian President Vladimir Putin and other high ranking Russian officials have been expressing increasing confidence in Russian military prospects in Ukraine against the backdrop of weakened and delayed Western support for Ukraine.[82] This public confidence may be posturing ahead of the March 2024 presidential elections and a part of Russian information operations aimed at demoralizing Ukraine and pursuing preemptive concessions from the West.[83] The Kremlin’s public confidence may also reflect the Russian command’s perception of what the Russian military can achieve while fighting a less-well-provisioned Ukrainian army. Delays in Western security assistance are likely forcing Ukrainian forces to husband materiel, and shortages appear to be degrading Ukrainian counterbattery fire.[84] ISW has previously assessed that the husbanding of materiel and uncertainty in operational planning may force Ukrainian forces to make tough decisions about prioritizing certain sectors of the front over sectors where limited territorial setbacks are least damaging.[85] The Russian command may hope that the east bank of the Oskil River is a sector that Ukrainian forces are willing to cede in order to continue responding to Russian offensive operations elsewhere in eastern Ukraine.

The longer the Russian military maintains the theater-wide initiative in Ukraine the more opportunity the Western Grouping of Forces has to achieve its operational objective of pushing Ukrainian forces off the east bank of the Oskil River. Ukrainian Main Military Intelligence Directorate (GUR) Head Kyrylo Budanov assessed on January 30 that Russian forces will fail to reach the administrative borders of Luhansk Oblast or the Zherebets River and will likely be “completely exhausted” by the beginning of Spring 2024.[86] Russian forces around Synkivka conducted a localized offensive operation for four months without showing any signs that the effort was near culmination, although it is possible that further significant intensification of the Russian operation throughout the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line could result in an operational culmination by the time Budanov identified. The Russian ability to conduct routine regroupings, replenishments, and rotations alongside the current operational tempo suggests that Russian forces may be able to continue operations along the Kharkiv-Luhansk axis for longer, possibly into summer 2024.

Budanov may be suggesting that muddy ground conditions in early spring 2024 would force the Russian operation along the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line to culminate since the ground will no longer be conducive to mechanized maneuver. Heavy spring rains can also interfere with drone operations, affecting both sides. Russian forces notably launched localized offensive operations throughout eastern Ukraine in Fall 2023, however, precisely at a time when similar ground conditions were not conducive to mechanized assaults in an effort to seize and maintain the theater-wide initiative following the Ukrainian summer 2023 counteroffensive.[87] WMD elements will likely try to take advantage of frozen ground in the winter to conduct mechanized assaults along the Kharkiv-Luhansk axis and may continue mechanized operations into spring 2024 since the multiple waves of mechanized Russian assaults around Avdiivka in fall 2023 suggest that the Russian command is willing to conduct such operations even in unfavorable conditions.[88] The Western Grouping of Forces may alternatively decide to continue operations through infantry-heavy assaults during the spring and resume mechanized maneuver as the ground and weather become more suitable in Summer 2024.

Russian forces could alternatively conduct the operation to reach the Oskil River in several active phases interspersed with operational pauses aimed at resting, replenishing, and preparing forces for resumed attacks in each direction of advance. The command of the Western Grouping of Forces has a wide range of options in determining both the tempo and the duration of its offensive effort precisely because the Russian military has the theater-wide initiative in Ukraine. Russian forces will be able to determine the location, tempo, operational requirements, and duration of fighting in Ukraine if Ukraine commits itself to defensive operations throughout 2024.[89] The Western Grouping of Forces may intend to conduct a much longer effort or resume it at a later date in case of its initial failure if it concludes that there is no credible threat of a Ukrainian counteroffensive in the area or elsewhere along the front.

Operational Effects of a Successful Russian Operation to Reach the Oskil River

The Russian seizure of the left bank of the Oskil River in Kharkiv Oblast would generate immediate operational benefits for Russian forces along the Kharkiv-Luhansk axis and throughout the theater while also setting favorable conditions for future Russian offensive efforts. Russian forces have not conducted offensive operations that have led to immediate operational-level benefits or set operational-level conditions for subsequent operations since Spring 2022.[90] Russian forces conducted nominally successful operations to seize Severodonetsk and Lysychansk in summer 2022 and Bakhmut in May 2023 and a nominally successful localized offensive effort to seize Avdiivka in February 2024, but those efforts have only generated limited tactical benefits for Russian forces.[91] A successful Russian operation to reach the Oskil River line would therefore be a significant inflection in over a year and a half of Russian campaigning in Ukraine.

Immediate Operational Effects

A successful Russian operation to push Ukrainian forces off the east bank of the Oskil River in Kharkiv Oblast would deprive Ukraine of a potential area from which to launch a future counteroffensive operation into northwestern Luhansk Oblast. Ukrainian forces previously attempted to advance towards Svatove and Kreminna after liberating Lyman in October 2022, and Russian forces committed a considerable amount of effort and manpower to stabilizing the line in the area and pushing Ukrainian forces back from the P66 (Svatove-Kreminna) highway.[92] The Russian seizure of all of Luhansk Oblast was one of the main objectives of the Russian Winter-Spring 2023 offensive effort in Luhansk Oblast and remains one of the Kremlin’s key objectives in eastern Ukraine.[93] Pushing Ukrainian forces off the east bank of the Oskil River in Kharkiv Oblast would not only achieve the Kremlin’s objective of occupying all of Luhansk Oblast, but would also likely ensure that Ukrainian forces were not able to reverse the Kremlin’s achievement anytime soon. Russian forces captured all of Luhansk Oblast in July 2022, a victory that the Kremlin soon had spoiled by the Fall 2022 Ukrainian counteroffensive’s advance into Luhansk Oblast.[94] The Kremlin likely hopes that positions along the Oskil River will prevent a scenario in which Russian forces have to routinely fight to retain or recapture Luhansk Oblast and allow the Kremlin to tout the occupation of all of Luhansk Oblast as a permanent victory.

The Russian seizure of the east bank of the Oskil River in Kharkiv Oblast would also likely secure several Russian ground lines of communication (GLOCs) in Luhansk Oblast from regular Ukrainian interdiction efforts. Russian positions along the P66 (Svatove-Kreminna) highway would be well out of range of Ukrainian tube artillery on the west bank of the Oskil River, and Ukrainian tube artillery would have to be deployed very close to the river to strike sections of the P07 (Svatove-Kupyansk) highway. Russian forces may also hope to be able to conduct counterbattery fire further into Kharkiv Oblast and push long-range Ukrainian artillery systems and HIMARS launchers out of range of Russian logistics facilities and GLOCs further in the rear. Moving Ukrainian fire further west would essentially allow Russian forces to turn a considerable section of Luhansk Oblast into near and deep rear areas and establish less vulnerable logistics to support operations further west and south of the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line. Ukrainian forces could still conduct long-range strikes against Russian targets in rear areas of Luhansk Oblast although Ukraine has limited numbers of long-range systems.

A successful Russian effort to seize the east bank of the Oskil River from Kupyansk to Oskil City would also create a defensible frontline very difficult for Ukrainian forces to attack and thereby allow Russian forces to transfer materiel and manpower to other efforts in Ukraine. The Oskil River would act as a significant water obstacle along a sizable sector of the frontline from the international border with Belgorod Oblast all the way to the Donetsk-Kharkiv Oblast border area. The only other sector of the frontline along a notable water barrier in Ukraine is the front along the Dnipro River in east (left) bank Kherson and Zaporizhia oblasts. The frontline along the Dnipro River has largely been inactive since the successful Ukrainian 2022 Kherson counteroffensive pushed Russian forces off west (right) bank Kherson Oblast in November 2022.[95] Ukrainian forces proceeded to conduct limited tactical activity along the Dnipro River and launched notably larger ground operations in October 2023 on the east bank of the Dnipro River that established a bridgehead in Krynky by November 2023.[96] The year of relative stasis along the Dnipro River allowed Russian forces to laterally transfer elements from east bank Kherson Oblast to the critical Russian defensive effort in western Zaporizhia Oblast in summer 2023 and permitted the Russian military to use rear east bank Kherson Oblast as a relatively secure area to train new forces and reconstitute degraded ones.[97]

The Western Grouping of Forces likely envisions a frontline along the Oskil River in Kharkiv Oblast resembling the frontline along the Dnipro River in some way. The Oskil River is nowhere near as wide or as deep as the Dnipro River (excluding in areas of the dried up Kakhovka Reservoir), and some sections of the Oskil River are narrow enough to ford with limited river crossing equipment and possibly even with armored vehicles. The Oskil Reservoir from southern Kupyansk-Vuzlovy to west of Oskil City is the Oskil River’s widest section before it narrows at the Oskil Hydroelectric Power Plant. This wide section of the Oskil River would be an easily defensible front, and even narrower sections of the river are still challenging terrain for Ukrainian forces to conduct counterattacks across. Ukrainian forces could more easily conduct cross-river tactical activity along the Oskil River than along the Dnipro River, but such activity would likely have poor prospects for reestablishing positions on the east bank of the Oskil River absent a larger Ukrainian crossing effort.

The relatively defensible frontline would likely require less Russian combat power to hold and allow the Russian command to transfer formations to other efforts in Ukraine or prepare for a subsequent offensive effort in northeastern Ukraine. The reduction in routine positional fighting along this frontline would allow the Russian command to transfer manpower and materiel currently operating in the northern sections of advance on the Kupyansk-Svatove-Kreminna line relatively freely without endangering Russian positions in the area.

Conditions Setting for Subsequent Operations

A successful Russian operation to advance towards the Oskil River would also set conditions for potential subsequent campaigns in northern Donetsk Oblast and/or eastern Kharkiv Oblast, and the Russian command may have designed the Winter-Spring 2024 offensive effort on the Kharkiv-Luhansk axis to prepare for successive campaigns in 2025 and beyond. The months-long effort to seize the east bank of the Oskil River will likely require the Western Grouping of Forces to consolidate its gains and rest and reconstitute over several months before committing to another large offensive operational effort. Russian forces would likely be unable to launch a subsequent campaign from the area until winter 2024-2025, and any Ukrainian counteroffensive operation would likely delay such a subsequent campaign well into 2025 or beyond.

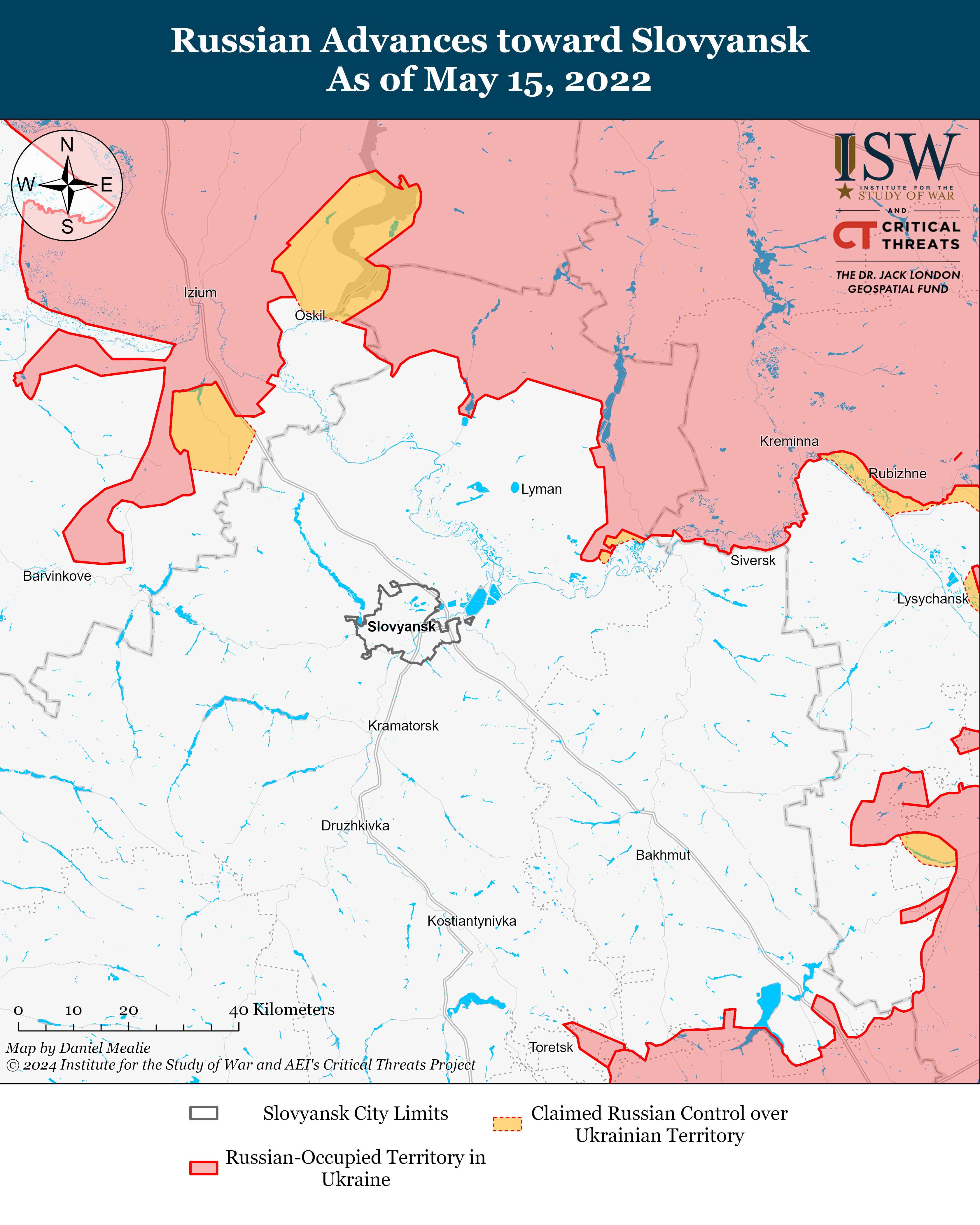

Russian forces previously attempted to seize the Ukrainian stronghold of Slovyansk in Spring 2022 as part of a wide campaign in eastern Ukraine that failed, and the seizure of the east bank of the Oskil River in Kharkiv Oblast would set several conditions for Russian forces to revive that effort. The Russian military intended to encircle Ukrainian forces in Donetsk Oblast in spring 2022 and attempted to conduct three corresponding maneuvers west from Severodonetsk-Lysychansk, south from Izyum, and north from Bakhmut to surround and seize Slovyansk.[98] The Russian command likely intended advances along the E40 highway (Izyum-Slovyansk-Bakhmut) highway and the capture of Slovyansk to facilitate the quick encirclement of Ukrainian forces in eastern Donetsk Oblast and open routes for further advances to the western borders of Donetsk Oblast.[99] Russian forces did not advance at the speed required to encircle Ukrainian forces, however, and by summer 2022 Russian forces prioritized the seizure of Severodonetsk and Lysychansk over the wider operational encirclement.[100] The Russian effort to drive on Slovyansk from Izyum culminated in mid-May 2022, and Russian forces likely intended to revive the effort from the Izyum-Lyman area at a later date.[101] Ukrainian forces liberated Izyum in early September 2022 and Lyman in early October 2022, however, effectively ending any Russian designs to resume a drive on Slovyansk.[102]

The Russian seizure of the east bank of the Oskil River in Kharkiv Oblast secures what would otherwise be a wide operational flank for a Russian effort to drive on Slovyansk from the northeast. A Russian effort to drive on Slovyansk from the Lyman direction would effectively be an offensive effort from an unstable salient unless Russian forces north of Lyman seize the Oskil River line. A Ukrainian presence along the east bank of the Oskil River would allow Ukrainian forces to counterattack a Russian drive on Slovyansk from the north, the west, and the south. The Russian seizure of the east bank of the Oskil River from Kupyansk to Oskil City would secure this operational flank, on the other hand, and allow Russian forces to attack along a wider front north of Slovyansk from positions backed by a secure Russian rear with the threat of Ukrainian counterattack confined to the south and west.

Advances towards Oskil City can set conditions for Russian forces to interdict and possibly cut the E40 highway between Izyum and Slovyansk. Oskil City and positions to the southeast are securely within tube artillery range of the section of the E-40 highway connecting Izyum and Slovyansk. Russian indirect fire in the area could disrupt the major Ukrainian GLOC connecting Kharkiv Oblast to northern Donetsk Oblast and force Ukrainian forces to reorient GLOCs towards Slovyansk from the northwest and west along smaller country roads or longer routes. The Russian command may also envision a subsequent operation from positions near Oskil City to reach and cut the E-40 highway. Interdicting and possibly cutting the E40 would recreate some of the effects of the northern envelopment of Slovyansk that Russian forces had initially created from positions near Izyum in Spring 2022.[103]

The Russian command could alternatively attempt to conduct a sweeping envelopment of Ukrainian forces in eastern Donetsk Oblast as it had initially planned in spring 2022 by conducting simultaneous maneuvers from the east bank of the Oskil River in Kharkiv and Donetsk oblasts and north from Bakhmut. The Russian command has previously shown an affinity for attempting wider operational maneuver across simultaneous axes in Ukraine, even if those efforts have been poorly planned and not parts of a cohesive operation with a coordinated objective.[104] The seizure of the east bank of the Oskil River in Kharkiv Oblast would allow Russian forces to reattempt the operational encirclement of eastern Donetsk Oblast using two operational offensive maneuvers instead of three. Russian forces could revive the initial effort to drive up the E-40 from Bakhmut while also attacking north and northeast of Slovyansk in a narrower and theoretically more manageable operational encirclement of eastern Donetsk Oblast. The prospects of Russian success in such a massive undertaking remain highly questionable as long as Ukraine retains anything like its current defensive capabilities, but the Kremlin might nevertheless try it.

The Russian command may also envision that the seizure of the east bank of the Oskil River could facilitate a subsequent drive further west into Kharkiv Oblast, although such an operation from these positions would likely be much more difficult than a drive on Slovyansk. The Kremlin has indicated that it aims to recapture territory in Kharkiv Oblast and occupy Kharkiv City.[105] The seizure of the east bank of the Oskil River in Kharkiv Oblast offers little change to the Russian military's current prospects for trying to secure parts of Kharkiv Oblast. Russian forces would need to attack across the Oskil River first and likely would need to operationally encircle west bank Kupyansk or capture Dvorichna (northeast of Kupyansk) before being able to advance further west into Kharkiv Oblast. Neither of those undertakings would be easy. Russian forces would need to cross large areas of open rural terrain interspersed with a few small settlements before reaching relatively sizable settlements such as Chuhuiv or Velykyi Burluk. Russian forces have not conducted such a long drive since the initial phase of the full-scale invasion and would be highly unlikely to be able to pursue such an effort.[106] Russian forces could alternatively try to capture Izyum from the southeast, although such an advance would either likely turn into a vulnerable salient or require similar wide operations across the Oskil River. These prospects for Russian advances into Kharkiv Oblast from the east bank of the Oskil River are as challenging as the prospects of advance elsewhere along the international border with Belgorod Oblast if not more so. If Russian forces are currently pursuing an operation to reach the Oskil River as a months-long conditions setting effort for a subsequent larger campaign, that subsequent larger campaign likely does not aim to advance further west into Kharkiv Oblast.

Conclusion

The Russian ability to conduct operationally significant offensive efforts is still largely dependent on the level of Western support for Ukraine. Well provisioned Ukrainian forces with superior capabilities have previously prevented Russian forces from making even marginal gains during large-scale Russian offensive efforts and have proven effective at causing lasting degradation to Russian logistics and combat capabilities.[107] Ukraine’s current capabilities are denying Russian forces the ability to restore the types of maneuvers required to conduct operationally significant advances, but many of those capabilities rely on key systems and materiel from the West and specifically the US.[108] The West has yet to provide Ukraine with certain capabilities that could allow Ukrainian forces to further constrain Russia’s ability to pursue operationally significant advances, particularly long-range strike capabilities that could degrade Russian logistics in depth and attack aircraft that could contest Russian aviation operations. Ukraine is attempting to rapidly expand its defense industrial base (DIB) to produce many of these capabilities itself, and Ukrainian forces are also developing technological innovations and adaptations that aim to offset Russian advantages in manpower and materiel.[109] These Ukrainian efforts will take time to produce results at scale, however, time that Russian forces will use to improve their own capabilities and to conduct potentially significant offensive operations such as their ongoing operation to reach the Oskil River line. Delays in Western security assistance have forced Ukrainian forces to husband materiel and have generated uncertainty in Ukrainian operational planning, vulnerabilities that Russian forces will increasingly exploit to facilitate gains on the battlefield.[110]

Ukraine’s ability to defend itself in the long-term relies on its ability not only to prevent Russian forces from seizing operationally significant ground but also to launch successful counteroffensive operations to liberate strategically vital areas.[111] The Ukrainian ability to seize and retain the theater-wide initiative and to liberate territory is an assured path to denying Russian forces opportunities to pursue strategically significant gains in Ukraine. Ukraine therefore needs security assistance that allows it to prevent ongoing Russian efforts to make operationally significant gains while also preparing for operations of its own that can liberate further Ukrainian territory.

[1] https://isw.pub/UkrWar021424 ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/kremlin%E2%80%99s-pyrrhic-vict... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[2] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[3] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[4] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[5] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[6] https://isw.pub/UkrWar010524 ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgr...

[7] https://isw.pub/UkrWar013024 ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgr...

[8] https://vk dot com/wall-170770667_203231 ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[9] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[10] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[11] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[12] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[13] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[14] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[15] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[16] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[17] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... https://t.me/zvizdecmanhustu/1608

[18] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[19] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[20] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[21] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[22] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-ass...

[23] https://t.me/zvizdecmanhustu/1608

[24] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[25] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-ass... ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-ass... https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-ass... ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-ass...

[26] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[27] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-ass... ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-ass... https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-ass... ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-ass...

[28] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[29] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[30] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[31] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... https://t.me/mod_russia/33901 ; https://t.me/voenkorKotenok/52888 ; https://t.me/milinfolive/113002

[32] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://suspilne dot media/665728-rosijski-vijska-vikoristovuut-novu-taktiku-na-limanskomu-napramku-recnik-21-ombr/ ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... https://t.me/zvizdecmanhustu/1491

[33] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... https://suspilne dot media/665728-rosijski-vijska-vikoristovuut-novu-taktiku-na-limanskomu-napramku-recnik-21-ombr/

[34] https://x.com/moklasen/status/1749105243277652257?s=20 ; https://t.me/BALUhub/7890

[35] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[36] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[37] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[38] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[39] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[40] https://t.me/zvizdecmanhustu/1491 ; https://t.me/zvizdecmanhustu/1468 ;

[41] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar101623 ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[42] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[43] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[44] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[45] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[46] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/kremlin%E2%80%99s-pyrrhic-... https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[47] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/kremlin%E2%80%99s-pyrrhic-vict...

[48] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[49] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[50] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/kremlin%E2%80%99s-pyrrhic-vict...

[51] https://isw.pub/UkrWar020224

[52] https://isw.pub/UkrWar021324

[53] https://isw.pub/UkrWar013124 ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar013024 ; https:... https://isw.pub/UkrWar010724

[54] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[55] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[56] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[57] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[58] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[59] https://isw.pub/UkrWar101623 ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar101623 ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ;

[60] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[61] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/kremlin%E2%80%99s-pyrrhic-vict...

[62] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/kremlin%E2%80%99s-pyrrhic-vict... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[63] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/kremlin%E2%80%99s-pyrrhic-vict... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[64] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/kremlin%E2%80%99s-pyrrhic-vict...

[65] https://isw.pub/UkrWar020124 ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar111723 ; https://isw.pub/UkrWar120923

[66] https://isw.pub/UkrWar110123

[67] https://isw.pub/UkrWar122623

[68] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/kremlin%E2%80%99s-pyrrhic-vict...

[69] https://isw.pub/UkrWar122623 ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgr... https://isw.pub/UkrWar021524

[70] Commercially available satellite imagery via Planet Labs LLC

[71] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[72] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[73] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[74] https://t.me/rybar/55875 ; https://t.me/creamy_caprice/3730 ; https:...

[76] https://t.me/rybar/55875 ; https://www.understandingwar.org/background...

[77] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[78] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[79] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[80] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; https://suspilne dot media/665728-rosijski-vijska-vikoristovuut-novu-taktiku-na-limanskomu-napramku-recnik-21-ombr/ ; https://x.com/moklasen/status/1749105243277652257?s=20 ; https://t.me/BALUhub/7890 ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgroun... https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[81] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/kremlin%E2%80%99s-pyrrhic-vict... https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[82] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...